A real community, but not without its challenges – Life of a New Forest commoner

The life of a commoner in the New Forest can be an incredibly complex one.

The tradition of turning out animals on the Forest goes back generations and it is a critical part of making the area become the unique and special place thousands enjoy every day.

Ponies, cattle, sheep and other livestock are turned out to graze and forage on the unfenced common land. Commoning plays a significant role in maintaining the New Forest’s internationally-important ecology and landscape.

The actions of the animals creates a wide range of national and international conservation designations which make it one of the most prized and cherished landscapes in the UK. But it is certainly not without its challenges as commoners are facing increasing pressures to their lifestyle from all directions.

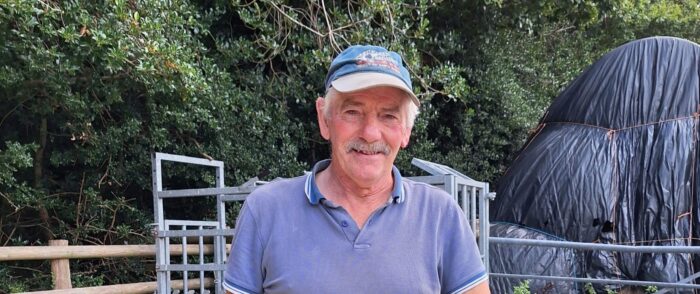

Commoner Bill Howells (pictured above), who lives in Norleywood in the south of the Forest close to Lymington, has been turning out animals on the commons for more than five decades. The 73-year-old lets us into his life and shares some of his more memorable experiences of the New Forest.

*The comments in this article are Bill Howells’ personal views, and not necessarily of the CDA*

“My mum and dad didn’t common, but I had uncles who did,” he begins. “At school I made friends with people who were in farming the forest, and they were commoners as well as farmers.

“I really got into the forest ways of turning out animals and eventually I was encouraged to keep some of my own and now I have been commoning for more than 50 years.”

Back-up grazing land

Commoners in the New Forest have to have access to back-up land when animals may need to be taken off the open access common land.

Owning or having access to back-up grazing is a key challenge for commoners as land is developed and high prices are paid for paddocks for recreational horse-keeping.

Bill said: “I was always interested in the cows and the ponies so I’ve got some of each. I’ve not got big numbers but enough which can be sustained by my land.

“It’s no good getting ahead of yourself and having too many animals because every now and then you get a run of bad luck when you’ve got to have them in.

“In winter, you have to have a lot in anyhow, especially the cattle who have to come in and be fed – and some winters when it’s hard there are some ponies in so you’ve got to realise the potential of your ground and not overcrowd it, basically.”

Making a living

The practice of commoning could be perceived merely as a hobby for those who love the countryside and tending to animals, but Bill says it has been – and continues to be – far more than that not just for him but other commoners as well who often have a full-time job alongside their commoning responsibilities.

“Commoning is a way of life, in the end,” he says. “A lot of commoners have got local jobs or are self– employed. There’s a variety of jobs.

“Although I worked full time for the Forestry Commission [now Forestry England], they were always pretty sympathetic to people who did common. It did always work well, me working for the Forestry because they understood that when you had animals, very rarely you might have to go home and sort an animal out so they allowed me to do that.

“They were always pretty good and sympathetic to our way of life.”

Traditional community

Bill continues: “You meet a lot of people around the Forest at events like drifts (when ponies are rounded up to be checked over) or pony sales, and local dances like we had years ago. You met people from right round the Forest.

“Even though they might live far away in the north of the Forest for example compared to here in the south in Norleywood, even though they’re not our neighbours, they are our commoning neighbours.

“Farmers wouldn’t necessarily know other farmers in the north of the Forest but as commoners, when we get together for different events it turns out to be a way of life.”

It is that tight-knit unit among commoners which helps keep the tradition going through thick and thin. Whether it’s the ever–changeable weather patterns, the cost of maintaining equipment or a disease outbreak affecting livestock, you can always rely on the hardy–souled commoners to ensure the Forest keeps ticking over.

Bill Howells with one of his ponies

“We are a community – we are spread out across the Forest but commoning is the common thread which keeps us all together and interested,” Bill explains.

“It is hard at times, not always financially but when we had Foot and Mouth we were shut down here in the Forest and we had to have our animals in, that was a difficult time. All animals were locked in their holdings and that was hard not just on the cattle but those looking after them as well. We were all in the same boat – farmers as well as commoners – so it was difficult then.”

Commoners who turn cattle and ponies out onto the Forest receive a subsidy payment under the Basic Payment Scheme (BPS) but following the UK’s departure from Europe, the government is phasing out the scheme by 2027.

Although a new Environmental Land Management Scheme (ELMS) is being developed by DEFRA, which would pay commoners based on the environmental benefits they deliver in their practice, it is unclear how this would be rolled out in the Forest.

The challenges to commoning in the New Forest, therefore, come from all angles and show no sign of abating. Bill fears it is the younger commoners coming through that could face some of the biggest difficulties to the way of life.

Land and housing

“A concern for me is the children – it’s having somewhere to set up and common from,” he says. “You’ve got to have a couple of acres [of land] at least.

“This is the biggest threat to commoning – the amount of holdings that are going out of commoning. The Verderers and the Commoners Defence Association have worked with Forestry England to keep places available for commoners to common from because they are ideal.

“Traditionally, when the keepers lived in them, they would usually have a few cows and ponies that went out into the Forest, so it’s vital Forestry England and the National Park Authority help build commoners’ holdings in special places, because you wouldn’t normally get permission on those green field sites.

“There are now about a dozen holdings being built along with the Forestry holdings but the private holdings are getting less and less. They’re just getting sold away.

“It’s surprising in the end the amount of places that have gone. In the end, that’ll be the biggest threat to commoning. For the youngsters or even other people who want to do it, they won’t be able to because there will be no where to do it from.

“Most of the land around the edge of the Forest would have been used as back-up land once and back-up lands are getting harder to get hold of, too.”

People pressure

With ever-more people coming to the Forest not just to visit the countryside but towns like Lyndhurst and Brockenhurst, the demands that come with them poses another serious threat to commoning.

Residents, too, have their responsibility in ensuring the Forest is preserved for future generations. Respecting the animals who are on the Forest is of utmost importance and educating the public about the dos and do nots when encountering livestock remains an ongoing battle.

“When new people come to the Forest they’re not sure how to treat the animals,” says Bill. “They put garden waste out and we get several cases of colic [in the ponies] a year. It’s just people don’t know they shouldn’t be doing it. They don’t realise the dangers, perhaps, to the animals.

A sign warning the public

“We’ve got a lot of pressure on the Forest. As well as the youngsters finding it hard to get going, there is the pressure of the tourism industry. It’s mounting up all the time.

“It’s the interaction with the animals. Sometimes people want to go up and pet them, and some animals may turn and retaliate. If people get in the way, they could get injured so it’s harder and harder [to manage].

“Years ago, people accepted they shouldn’t be touching the animals but now it’s changed and that puts the onus back on the commoner. It puts you in a difficult position because you don’t want your animals to injure anybody but then again you want your animals to be out there to do the conservation job they’re doing. It’s a difficult one.”

Animal accidents

Sadly, commoners know all too well about losing animals with road accidents often leading to a severe injury, if not death, having been hit by a vehicle.

Various initiatives are in place to help reduce these incidents, such as a ‘salt lick’ scheme which aims to encourage ponies – who love the road salt or grit – away from the roadside, Operation Mountie run by the police and partners which targets speeding drivers; and large signage warning drivers to slow down, but despite these efforts, animals casualties continue.

According to the Verderers’ figures, in the past five years an average of 47 animals have died each year as a result of being involved in a road accident. In addition, an average of 22 animals have been injured each year of the same time frame.

The salt lick scheme is one initiative trying to reduce the number of animal accidents

“Over the years I’ve had a few animals involved in road accidents, I think all commoners have,” reflects Bill. “I’ve had two or three foals killed, two cows, about four mares, so I’ve probably lost around 10 animals overall. But unless your animals are in a place which is right away from the road, then you might be lucky but I would say most commoners have had some casualties.

“There are campaigns going and police have been doing a lot of checks which is good and I think it’s made people steady up but we’re always going to have accidents. It’s difficult to educate everybody to the degree they need to be.

“When you go round a bend or there’s a dip, or it’s foggy, whenever you’re driving you must always think there’s going to be a pony. Some people drive with an instinct of being careful but for others, sadly it’s the last thing on their minds. I’m not saying they’re all speeding, they’re just not driving carefully enough for the Forest.”

Following the seasons

While no two days are the same for New Forest commoners, there are certain practices and routines to be followed at different stages of the year.

“In the summer, the animals are out so we [commoners] are making hay or silage,” says Bill. “We’re repairing fences and really just getting ready for the winter. In autumn we go to the drifts where we look at the ponies and in winter it’s into the routine of feeding the animals every day if you have cattle.

“If you have ponies, people probably go out at least once a week to check on them and monitor them, and get them in if they need to. Cattle are the most intensive side of commoning – they have to be fed every day, cleaned out, bedded and that takes the time in the winter.”

Maintaining a rare breed

Stallions are turned out annually to keep the New Forest pony going as a breed but also to control the number of foals born each year.

Bill says: “The stallions were out for about six weeks last year. We were lucky we got some filly foals but long term we’re getting less and less stallions because people find it more difficult to keep them.

“We’ve got to look at the numbers seriously and see if we’ve got enough stallions to go out, to maintain the herd. Five thousand mares, forest wide, is a good number and we need about 2,000 cattle. They are numbers that the Forest could sustain but it’s difficult.”

Along with organisations such as the New Forest National Park Authority and Forestry England, commoners work with certain groups, such as the agisters, on the ground to manage livestock.

There are a total of five agisters who work for the Verderers and each one looks after a certain patch within the forest. They will be alerted to any sick or injured ponies and conduct various administrative tasks like collecting marking fees (an annual fee which commoners pay to keep their animals on the forest).

“We’re in contact with the agisters all the time,” says Bill. “And I know the elected Verderers because they are the ones voted in by the commoners. They are from the commoning community.

“We don’t always agree with the Verderers but they oversee commoning for us in the Forest and it gives our community a bit of structure. If anyone outside the forest wants to know the answer to a question, it’s better the Verderers are there to talk for us.

“It’s difficult balancing things but the agisters are very good and if you’ve got an injured pony, they’ll usually phone you and will accept as long as you get there that evening, after work, you can deal with it or a member of your family can. They’re pretty sympathetic and it all works pretty well together.”

Future funding

The life of a commoner in the New Forest, therefore, is full of ups and downs and everything in between. There can be little doubt about the importance of their work, not only in keeping the Forest landscape in shape but also maintaining the tradition which goes back centuries.

And while commoners’ financial future is uncertain as one Government funding scheme comes to an end post-Brexit, Bill is optimistic their steely resolve, dedication and love for the area and livestock will always counter any threats to commoning in the strongest possible terms.

“We’re trying to work out how we’re going to get subsidies for the future – I think it would be in a pretty perilous state if there was no subsidy at all,” he warns.

“I don’t think people would keep the animals. Everything is so expensive at the moment but when you are in commoning and need extra things to what a normal person would need like fencing, cattle-handling equipment, diesel for your tractor…without subsidy the amount of commoners would really dwindle.

“There has got to be some recognition that if the government and people want the Forest to stay in the same state it’s in by being grazed, then inevitably there needs to be some money put into it. I don’t know how it’s going to work, but there is a need.”

He continued: “We are not in it for money, it’s the pleasure we get of going out into the Forest and seeing our animals and seeing them contribute to the landscape.

“In the future, I hope there is some sort of subsidy system to encourage the youngsters to common. Unless somebody recognises we do need a bit of subsidy money, I think in 20 years’ time numbers [of commoners] could dwindle. I don’t think it [commoning] would pack up altogether but it would be harder and harder for the youngsters as well to justify it.

“But I’m not too doom and gloom, everything is still okay. I want the subsidies to be given to the right people though, to encourage them in a certain way – not to overstock but to just be good commoners.

“I hope we can sort it out to benefit the Forest, rather than just a few commoners with a load of money for a few years. That’s not long-termism. You want youngsters settled, have a holding, have a job and keep some animals to keep the tradition going, that’s what I want the subsidy to be for.

“It’s not to make people rich, I wouldn’t want that. I would like it to benefit the Forest and help sustain it. It’s what makes the area unique.”

Members Login

Latest Tweets

Latest Tweets

Follow us

@realnewforest 4h

Icilibus sam quas aut eriatem nume corepta auta conet officaborem quodi corepta auta conet officaborem quodi apernat ectlpa dolorpiaecus.

@realnewforest 4h

Icilibus sam quas aut eriatem nume corepta auta conet officaborem quodi corepta auta conet officaborem quodi apernat ectlpa dolorpiaecus.

@realnewforest 4h

Icilibus sam quas aut eriatem nume corepta auta conet officaborem quodi corepta auta conet officaborem quodi apernat ectlpa dolorpiaecus.

With thanks for support from