FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

About Commoners

+Why should commoners’ get special housing treatment?

+ In 1991 the Illingworth Report, which concluded a review of New Forest grazing for the Government, came to two important conclusions in response to widespread concern at the decline of the grazing upon which the special qualities of the New Forest depend. Firstly, it determined that sustaining the vocational commoning system was the only viable way to ensure that the New Forest continued to be grazed. Sustaining commoning, however, would depend upon ensuring the people willing to continue the system have access to homes and land. It called, therefore, for everything possible to be done to achieve this. This included the prioritisation of cottages managed by the Forestry Commission for commoning tenants, given the decline in commercial forestry needs, support for local charitable and social landlords. Since then the Commoners’ Dwelling Scheme has allowed families who already own some land to create new holdings on this land, under very strict conditions, and permanently tied to commoning. This scheme is only available to those who have sufficient land, who are willing to sign over their freehold on some of it forever, and can raise the funding to build a home and appropriate outbuildings. A quarter century after the Illingworth Report there has been much less success in developing commoners’ holdings for rent.

In 1991 the Illingworth Report, which concluded a review of New Forest grazing for the Government, came to two important conclusions in response to widespread concern at the decline of the grazing upon which the special qualities of the New Forest depend. Firstly, it determined that sustaining the vocational commoning system was the only viable way to ensure that the New Forest continued to be grazed. Sustaining commoning, however, would depend upon ensuring the people willing to continue the system have access to homes and land. It called, therefore, for everything possible to be done to achieve this. This included the prioritisation of cottages managed by the Forestry Commission for commoning tenants, given the decline in commercial forestry needs, support for local charitable and social landlords. Since then the Commoners’ Dwelling Scheme has allowed families who already own some land to create new holdings on this land, under very strict conditions, and permanently tied to commoning. This scheme is only available to those who have sufficient land, who are willing to sign over their freehold on some of it forever, and can raise the funding to build a home and appropriate outbuildings. A quarter century after the Illingworth Report there has been much less success in developing commoners’ holdings for rent.

The New Forest has long been an expensive landscape, but this has accelerated since National Park status was imposed. Today the average property value within the National Park is more than 15 times the average local income. But to common on any scale working locally is imperative. A commoner must be able to step out of work at any time to deal with their livestock. Combining a local working life with keeping cattle and pigs is particularly challenging, meaning that the need to work locally and flexibly is imperative. Natural England require that cows form at least 25% of the livestock on the Crown Lands of the New Forest, as the mix of grazing animals is vital to the condition of the protected landscape and the exceptional biodiversity it supports. This could not be achieved if commoning was left to become the sole preserve of a wealthy local population using the common rights attached to their properties to turn out a small number of New Forest ponies. The Commoning Census carried out each decade shows that these people tend not to stay in commoning for very long; the hardships and commitment to maintain even hardy semi-feral ponies, with its cost, trials and tribulations, is certainly not for everyone. Sustaining the extensive grazing of the New Forest requires a large number of people, of all ages, scattered throughout the Forest, working and living locally, and with a lifelong commitment. This, in turn, requires appropriate small homes close to the grazing land, and sufficient facilities to keep a mix of Forest livestock.

In the end everyone benefits from sustaining commoning. Maintaining access to a small number of homes and land for people willing to make the commitment required seems a very small price to pay for keeping the New Forest accessible, rich in nature, and maintaining its unique cultural heritage.

Can I become a commoner?

+Yes. Anyone can be a New Forest commoner. Commoners come from all walks of life, and live all around the New Forest. Whilst the rights are linked to land and buildings, you only need to “occupy” the land to qualify. This can be shared, rented or owned, and of any size. It is, of course, important that you also have access to sufficient “back-up” land and facilities when you need it, so you can properly care for any animals that are allowed to graze the New Forest. There is a successful mentoring scheme, in which experienced commoners help young and new commoners learn how to do it well.

How is the Boxing Day Point-to-Point good for the New Forest?

+

The annual point to point is the year’s most important social gathering for commoning, serving multiple purposes beneficial to the New Forest.

The Point to Point:

- Is a showcase for the extraordinary abilities of the rare breed New Forest Pony, hence the restricted races and prizes for registered New Forest ponies, and New Forest first-cross and part-bred horses.

- Provides a strong incentive for commoners to help on horseback in the essential autumn round-ups, known as “drifts”. The drifts are vital to the management of the grazing ponies, and volunteer riders are crucial to assist the agisters. Riders build knowledge of the terrain away from their local haunts, and their riding ponies get used to working at speed in company – important attributes for riding the point to point.

- Brings together the commoning community, to chat, to show off their ponies, their commoning skills, and to have fun. This is the only occasion in the year that brings together most commoners. The sense of community, and the focal point, is an important draw for young commoners to remain involved in commoning amidst increasingly busy lives at school, college or work.

- A point to point, testing the Forest knowledge and riding skills of commoners has been ru as a formal event for more than 100 years. It is an important and popular demonstration of the unique cultural heritage of the New Forest as a surviving unenclosed landscape.

- Is run by the local charity, the New Forest Pony Breeding and Cattle Society (Charity No. 1064746). Any proceeds from the event are used to support the important work of the charity.

The extraordinary biodiversity and cultural heritage of the New Forest depend upon the continuation of the vocational system of livestock grazing. It is a vocation that is increasingly demanding, in both time and money.

The event itself is very carefully managed to minimise its impact on the landscape, under terms agreed with Forestry England. It takes place outside the growing and nesting seasons, with careful consideration and months of preparation given to the finish location, for vehicular access and parking. Because of this none of the finish sites have ever experienced any lasting impact from the event.

Commoners care deeply about the New Forest, and are particularly careful not to damage the grazing upon which their animals depend, nor to leave anything behind. The effort put in to the annual point to point ensures that it continues to make a very positive contribution to this very special landscape. The biggest risk of harm to the New Forest is the decline of vocational commoning amidst the pressures of modern life – The Point to Point is of huge value in encouraging local people to maintain their commitment to grazing animals on the landscape, with a real sense of identity and community.

Do commoners have to pay to graze animals on the Forest?

+Marking fees are payments made on each animal turned out onto the Forest for the present year. They are set by the Verderers and help towards the agisters’ (q.v.) salaries. No animal over 6 months age is allowed to be turned out on the Forest before the marking fee is paid and the animal marked by the agister.

About Commoning

+Is commoning profitable?

+ No. Commoning is a vocational commitment, requiring people to make a substantial commitment of their own time and money. Most commoning activity is unseen, whether that is the annual rituals of TB testing of cattle, regular checking of grazing stock, hay making for winter fodder, worming, castrating young colts, or halter-breaking each year’s foals. The most visible activities are the summer shows, when commoners compete on the quality of their animals, the colt assessments in the Spring, and the Autumn round-ups (known as drifts). All of this, of course, costs money as well as time. Veterinary bills can come randomly and be substantial but essential.

No. Commoning is a vocational commitment, requiring people to make a substantial commitment of their own time and money. Most commoning activity is unseen, whether that is the annual rituals of TB testing of cattle, regular checking of grazing stock, hay making for winter fodder, worming, castrating young colts, or halter-breaking each year’s foals. The most visible activities are the summer shows, when commoners compete on the quality of their animals, the colt assessments in the Spring, and the Autumn round-ups (known as drifts). All of this, of course, costs money as well as time. Veterinary bills can come randomly and be substantial but essential.

The biggest cost of commoning is probably obtaining and maintaining back-up grazing. The New Forest is the country’s most expensive National Park, where grazing land has reached £60,000 an acre. Commoners use a mix of renting, borrowing, and ownership for their essential back-up land. If they have too little for haymaking then they will probably also need to buy in hay or silage for winter fodder, and for other times when their animals are not turned out to graze the New Forest. There is also, of course, a substantial investment in buying and maintaining equipment, whether stock trailers and 4x4s, or tractors and land-management machinery. Without this then the costs of hiring a contractor can mount very quickly.

Checking stock is best done from horseback, and these are essential for the drifts. The costs of horsekeeping, to support commoning activities, can be substantial. Whilst those who get glimpses of commoners riding out checking stock on a sunny day may see this as a “hobby”, it certainly does not feel that way at the end of a winter working day or when things go wrong- the need to catch and bring home a sick or injured animal will always come about at the least convenient time.

A huge effort has gone into improving the quality of the animals that graze the New Forest, but a substantial effort is needed if they are to achieve a respectable price when sold. The effort of halter-breaking a pony foal might, for example, add £50 to its value, but will add much more for a commoner’s pride at the saleyard. The Commoning Census, repeated each decade, reveals the motivations of commoners: Pride in the New Forest, a desire to be part of the “real” New Forest, and a commitment to sustaining this ancient practice.

The Basic Payment Scheme (BPS) has certainly helped reduce the costs involved in a commitment to commoning, and has done much to achieve the boost to cattle numbers demanded by Natural England. As a Europe-wide scheme the BPS does not, however, require any commitment to commoning. Any farmer who obtains BPS entitlements over the New Forest, can ask the agisters to mark their cattle for the New Forest, and claim over the Rural Payments Agency’s “eligible area”. The BPS is based solely on this area calculation, giving a fixed amount per hectare, shared amongst however many people claim according to the number of “Livestock Units” marked (A cow is one livestock unit). As a result the Verderers Marking Register increases each year, and the amount a commoner receives for each animal declines. In 2017 this bizarre system produced support of approximately £412 per marked cow and £247 per pony. Additionally, the standard calculation of the “eligible area” is unstable in the context of the New Forest, where livestock graze a much wider variety of habitats than is normal on improved farmlands. This systems and its instability is neither desirable nor sustainable. Support intended for the New Forest should work to the benefit of the New Forest.

Since 2017 the CDA has been working with local partner organisations to press for change – towards a system that improves New Forest habitats, provides the necessary support to commoning, We would like to see a system that uses the current Verderers’ Higher Level Stewardship (HLS) Scheme as its starting point, support systems that are locally designed and managed, sympathetic to the New Forest. Most importantly, it must ensure that the common grazing of a mix of livestock remains sustainable within England most expensive National Park, with a challenging mix of high average costs and low average incomes in the local economy.

Are all the foals born in Spring?

+No. Most of the foals born on the Forest will be sired by the previous year’s stallions that were selected to run on the Forest. After the commoners demanded a system to control the quality and quantity of foals, leading to the Stallion Scheme, not only has the number of stallions been dramatically reduced, but also the time they spend out on the Forest. Now they are only out for a few weeks in late Spring. This means that most of the foals are born within a short time-frame almost a year later.

But, there is nothing to prevent commoners from choosing to put a mare with a stallion off the Forest. They may want to achieve a particular bloodline, for example, or to produce a cross-bred pony to suit their future needs. This means that foals can still be born at any time of year, although this is now quite rare. Of course, the timing of the stallion turnout is set to make things as positive as possible for the mare and foal; when there is good vegetation growth, the weather is at its most benign, and there are several months before the round-ups, known as “drifts”. Foals born at other times will need the owners to keep a very close eye on their progress. They may turn them out for a short time just to build their experience of the Forest, learning to graze the variety of vegetation and build experience of life on the Forest. They may turn them out to take advantage of unseasonably good weather, allowing the mare and foal to benefit from a more natural envir0nment than at home and resting their home grazing for a while.

But, there is nothing to prevent commoners from choosing to put a mare with a stallion off the Forest. They may want to achieve a particular bloodline, for example, or to produce a cross-bred pony to suit their future needs. This means that foals can still be born at any time of year, although this is now quite rare. Of course, the timing of the stallion turnout is set to make things as positive as possible for the mare and foal; when there is good vegetation growth, the weather is at its most benign, and there are several months before the round-ups, known as “drifts”. Foals born at other times will need the owners to keep a very close eye on their progress. They may turn them out for a short time just to build their experience of the Forest, learning to graze the variety of vegetation and build experience of life on the Forest. They may turn them out to take advantage of unseasonably good weather, allowing the mare and foal to benefit from a more natural envir0nment than at home and resting their home grazing for a while.

Of course, if you spot a mare and foal in poor condition at any time of year then do contact the Verderers (there is a form on their website). But there is no need to panic especially because a mare and foal are out at an unusual time. It has simply become a modern rarity.

Why isn’t the New Forest pony the only breed on the Forest?

+

Commoners have the right to turn out any unshod equine to graze the New Forest. The only exception is that it must not be an entire male. It does not need to be a pure-bred New Forest Pony. Each commoner is responsible for their own animals, and is free to decide what is best for them and for their animal’s welfare. Some breeds will be less hardy than a New Forest pony, and some as hardy. Whatever the breed they will have to be taken home if and when they need additional care. Donkeys too have a very long history in the New Forest. You will see donkeys, shetlands and coloured ponies grazing the New Forest during the year, and being sold at the Beaulieu Road sale-yard. Every equine mouth helps maintain the habitats of the New Forest through their grazing, and each breed grazes a little differently. It all helps.

Each commoner will have their own plans for their Forest-run ponies, some will stay to graze the Forest, some will become their own riding, driving or showing ponies, and some will be sold to new owners. This is a genuine case of “horses for courses”. A little variation in the animals that graze the Forest is simply a reflection of the diversity within commoning.

Of course, the New Forest pony is the best adapted to grazing the extraordinary mosaic of habitats, ranging from coastal marshes and bogs, to dry heaths, hedgerows and woodlands. Breeding has been carefully managed to ensure that the qualities of the New Forest pony are maintained, particularly through the selection and control of stallions; they are all pure-bred, pedigree New Forest, rigorously inspected and licensed. Stallion numbers on the New Forest are adjusted each year according to market conditions for the sales. The New Forest Pony is now included on the list of native rare breeds. Since the 1980s the commoners have instigated successive schemes to encourage the keeping of high quality registered New Forest mares.

Most foals bred on the New Forest are registered with the Breed Society, whether as pure-bred or cross-bred. Around 9 in 10 of the foals registered each year by the Breed Society are pure-bred New Forest ponies*. Of course, any Shetlands and Exmoors etc., are registered with their respective societies instead of ours. All foals must be registered and “Forest-bred” remains a very desirable attribute, and is controlled by the Society. The first volume of the New Forest Pony Stud Book was published in 1910.

There are several pieces of folklore around the development of today’s New Forest pony breed. In her wonderful book “New Forest Ponies” Dionis Macnair says:

“Every native breed has the myth of the stallion that swam ashore from the Armada – certainly not possible in the New Forest; there were no wrecks in the South Coast. As we know there was a Royal Stud in the Forest it seems very probable Spanish stallions stood here and were crossed with the local ponies to breed these more athletic mounts. This would be the first chance to try them in action. We also have stories of veteran army horses turned out on the Forest”

For more on the story of the New Forest Pony take a look at the Breed Society website

*In 2018 there were 15 selected stallions turned out for up to 37 days; this was the highest number and length of time for some years. As a result, In 2019 the Breed Society registered 413 foals, of which 373 (90%) were pure-bred New Forest ponies.

Are there commoners in other places?

+The use of ‘common’ land for grazing and other farming practices is widespread across the world. It also used to be widespread in the UK, with many areas of ‘manorial waste’ used to graze livestock, and collect fallen timber or other natural goods, as part of a peasant and smallholder based economy. The moves to enclose common land across much of lowland Britain started in the eighteenth and accelerated in the nineteenth century, when a series of enclosure acts deprived many small farmers of a large part of their income and forced them into the country’s growing industrial towns. Grazing on common land now survives in a number of restricted areas, mostly in the uplands of England, Wales and Scotland. Many of these areas are now designated as national parks and make up some of the country’s most precious landscapes.

More information about commoning in the British Isles can be found on the website of the Foundation for Common Land at: http://www.foundationforcommonland.org.uk/

How is the Boxing Day Point-to-Point good for the New Forest?

+

The annual point to point is the year’s most important social gathering for commoning, serving multiple purposes beneficial to the New Forest.

The Point to Point:

- Is a showcase for the extraordinary abilities of the rare breed New Forest Pony, hence the restricted races and prizes for registered New Forest ponies, and New Forest first-cross and part-bred horses.

- Provides a strong incentive for commoners to help on horseback in the essential autumn round-ups, known as “drifts”. The drifts are vital to the management of the grazing ponies, and volunteer riders are crucial to assist the agisters. Riders build knowledge of the terrain away from their local haunts, and their riding ponies get used to working at speed in company – important attributes for riding the point to point.

- Brings together the commoning community, to chat, to show off their ponies, their commoning skills, and to have fun. This is the only occasion in the year that brings together most commoners. The sense of community, and the focal point, is an important draw for young commoners to remain involved in commoning amidst increasingly busy lives at school, college or work.

- A point to point, testing the Forest knowledge and riding skills of commoners has been ru as a formal event for more than 100 years. It is an important and popular demonstration of the unique cultural heritage of the New Forest as a surviving unenclosed landscape.

- Is run by the local charity, the New Forest Pony Breeding and Cattle Society (Charity No. 1064746). Any proceeds from the event are used to support the important work of the charity.

The extraordinary biodiversity and cultural heritage of the New Forest depend upon the continuation of the vocational system of livestock grazing. It is a vocation that is increasingly demanding, in both time and money.

The event itself is very carefully managed to minimise its impact on the landscape, under terms agreed with Forestry England. It takes place outside the growing and nesting seasons, with careful consideration and months of preparation given to the finish location, for vehicular access and parking. Because of this none of the finish sites have ever experienced any lasting impact from the event.

Commoners care deeply about the New Forest, and are particularly careful not to damage the grazing upon which their animals depend, nor to leave anything behind. The effort put in to the annual point to point ensures that it continues to make a very positive contribution to this very special landscape. The biggest risk of harm to the New Forest is the decline of vocational commoning amidst the pressures of modern life – The Point to Point is of huge value in encouraging local people to maintain their commitment to grazing animals on the landscape, with a real sense of identity and community.

What is the origin of commoning in the New Forest?

+Following the Norman Conquest William the Conqueror designated the area we now call the New Forest as a Royal Hunting reserve (between 1066 and 1068). The designation resulted in the introduction of Forest Law which meant that the land couldn’t be enclosed for agriculture or housing – and introduced other controls that might interfere with the King’s hunting rights. In exchange for these controls, the Law established common rights to be exercised by those who owned or rented land within the hunting reserve.

However, the right to graze animals on common land was widespread across the country at least until the end of Feudal times. Prior to the introduction of Forest Law, the New Forest, like many other areas of Britain was made up of large tracts of land whose common usage was an essential part of peasant farmers’ economy.

From the 12th century onwards, increasing areas of land over which common rights were exercised were incorporated into the great estates of the nobility and church. Over succeeding centuries, the common agricultural land that had supported the lives of tenants and copyholders, was enclosed and converted to pasture at the whim of the landowner. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the enclosure of manorial waste and commons was accelerated under a series of Enclosure Acts, until very little land over which common rights operate now exists in lowland Britain.[1]

The New Forest was not seriously threatened by inclosure until, in 1851, an act of parliament (the Deer Removal Act) introduced a ‘rolling power of enclosure’ which threatened to turn all the best land in the Forest into timber enclosures and sell the remainder. As the full implications of the Act became apparent, local landowners whose rents were increased through the added income provided to smallholders by access to the common grazing, organized opposition through a petition to parliament in 1867. Shortly afterwards, this group founded the New Forest Association and set about preventing further inclosure. Using the growing interest in landscape, the Association galvanized the power of public opinion to save the Forest from inclosure and build the foundations for the 1877 New Forest Act which re-instated the powers of the Verderers and assured the future of the New Forest.[2]

During the latter part of the nineteenth century the urban populations around the New Forest spread considerably, while the development of the railway through the Forest and extension of the road network meant that new residents started to move into the villages in the Forest itself. Increasingly, commoners and their animals came into contact with people who had little understanding of their way of life, and often found the presence of their animals on roads and village greens a nuisance. In 1909 the New Forest Commoners Defence Association was founded in response to the increasing level of such conflict, and has continued to defend the rights of its members against numerous threats to the present day.

[1] Hammond, J L and Barbara (1920) The Village Labourer 1760 to 1832: A Study in the Government of England before the Reform Bill. Longmans, Green and Co, London. [2] Pasmore, Anthony (1977) Verderers of the New Forest: A History of the New Forest 1877-1977. Pioneer Publications, Beaulieu.

How do commoners know which animals are theirs?

+Commoners know their animals and can usually recognise them without difficulty. Each pony is branded with the owner’s brand and each cow or sheep carries identification tags in its ears. Donkeys have a brand or an ear button. The local agister is familiar with the animals in their area and can often identify most of them individually, too.

Do commoners have to pay to graze animals on the Forest?

+Marking fees are payments made on each animal turned out onto the Forest for the present year. They are set by the Verderers and help towards the agisters’ (q.v.) salaries. No animal over 6 months age is allowed to be turned out on the Forest before the marking fee is paid and the animal marked by the agister.

What are the common rights of the New Forest?

+Commoners of the New Forest are those who occupy land or property to which attaches one or more rights over the Forest. These rights are:

- Common of pasture: commonable animals – ponies, cattle, donkeys and mules – are turned out into the Open Forest;

- Common of pasture for sheep: although some of the large estates have this right, it is infrequently exercised;

- Common of mast: the right to turn out pigs in the autumn pannage season which lasts for at least 60 days, to devour the autumn harvest including beech mast, chestnuts and acorns – this provides food for the pigs and reduces the threat to ponies and cattle from the poisonous acorns;

- Estovers (Fuelwood): the free supply of a stipulated amount of firewood to certain properties;

- Common of marl: the right to dig clay to improve agricultural land – this right is no longer exercised;

- Common of turbary: the right to cut peat turves for the Commoner’s personal use – this right is no longer exercised.

Caring for the Animals

+How do we know which stallion is the sire (Dad) of which of the foals on the Forest?

+In most cases, identifying the correct sire of a foal is fairly straightforward. The number of stallions that are turned out in the Forest for the breeding season is so small these days and they are ‘watched’ quite closely. Agisters, Commoners and some of the interested general public take notice of which areas the stallions visit; and which mares visit them! A mare that runs in the same area as a stallion tends to get in foal to that stallion.

But there are a number of other points that are used – and checked – when the foal has the sire’s name added to his registration papers.

Firstly, we use the coat colours – of sire, dam and foal.

With increased understanding of modern colour genetics we can sometimes confirm – or eliminate – a sire. One example of this is that a grey foal must have a grey parent, so if the mother isn’t grey then the father has to be.

Then we can look at the markings of the foal.

This can be the amount (and placing) of the white markings, the whorls and perhaps something like the ‘ermine spots’, which are black spots on the white socks.

And then there is the ‘general look’ of a foal. Sometimes it is just so obvious because the foal looks just like his daddy! An experienced eye, seeing several foals by the same sire, can pick out the similar shape of the head or feet, the set of the neck or hind leg etc etc.

And finally, there is DNA typing.

For various reasons, there are a number of ponies that are DNA sire checked, including some random checks carried out by the NFPB – and this can help to confirm ‘what we are looking at’; i.e that X stallion does put 3 socks on his foals, despite having none himself.

The other point to always bear in mind concerning foals on the Forest: – the mare might have got in foal while she was at home, on her owner’s holding – just because they are out on the Forest now, doesn’t necessarily mean that they were sired there.

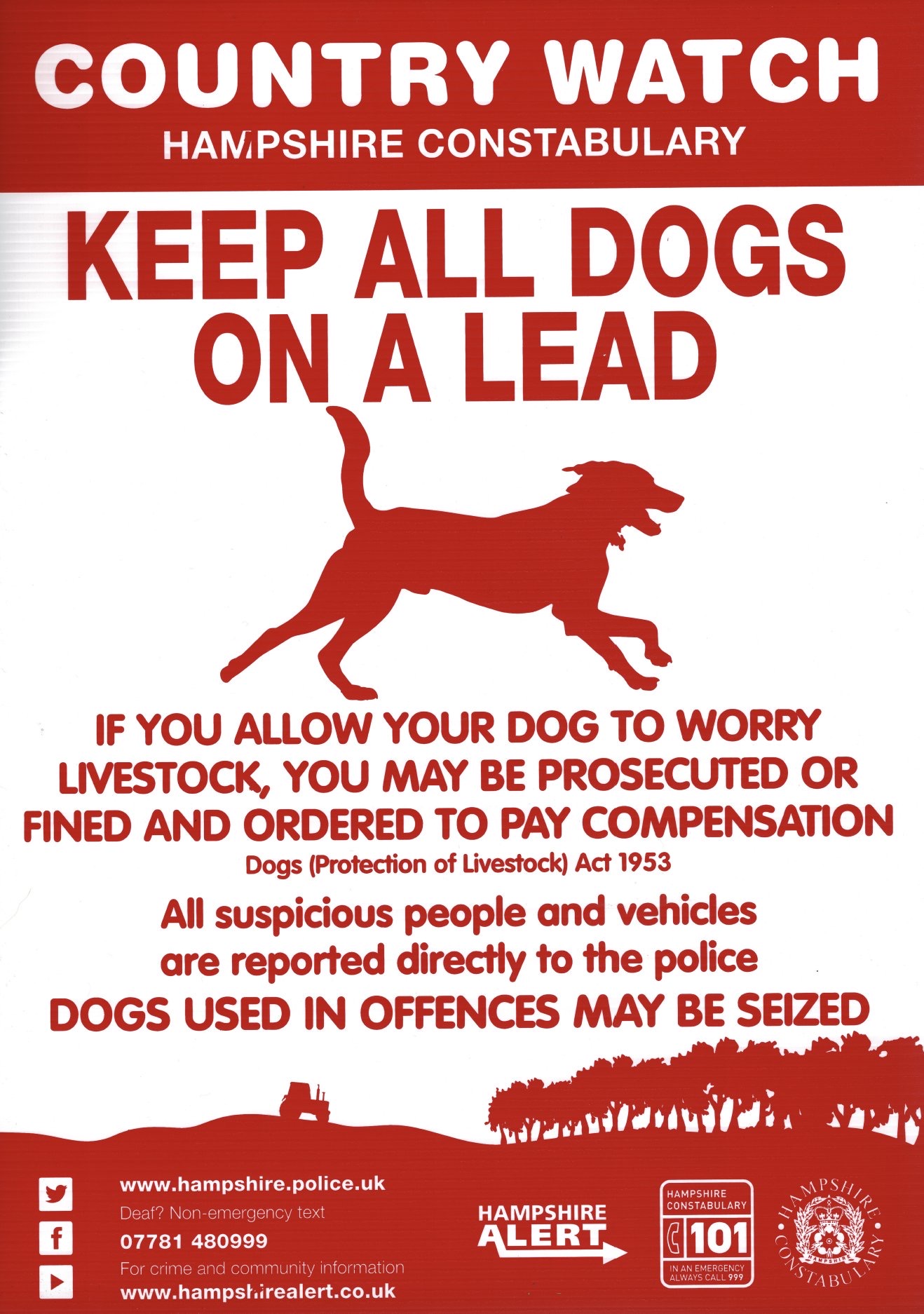

My dog is used to ponies and cows, so why should I worry?

+The grazing animals don’t know your dog. They only know the previous dog that came past.

If they have been worried by someone else’s dog then yours will be viewed as a predator. Cows and ponies are known to charge a dog if they feel threatened. We can all fall victim to someone else’s poor dog control. As with many offences, it is often the innocent who suffer.

It is vital to avoid this risk. The law requires dogs to be under close control around livestock; on a leash if necessary. They must be put on a lead around sheep. But it is also important to give them a lot of space. Cows will often leave their calves beside a bush, whilst they wander off to graze. Keep a good lookout for this, and do your best to avoid passing between them, and to keep you and your dog well away from the calf.

It is vital to avoid this risk. The law requires dogs to be under close control around livestock; on a leash if necessary. They must be put on a lead around sheep. But it is also important to give them a lot of space. Cows will often leave their calves beside a bush, whilst they wander off to graze. Keep a good lookout for this, and do your best to avoid passing between them, and to keep you and your dog well away from the calf.

However well-behaved your dog, always #KeepYourDistance from livestock. This will keep you safe, and avoid the risk of inadvertently worrying the animals.

If you see a dog worrying New Forest livestock please call the Police on 101 or (in an emergency 999), with as much detail as possible. Worrying is a criminal offence under the byelaws and under the Dogs (Protection of Livestock) Act. It not only causes suffering to the animal, but it puts all of us at risk. An out-of-control dog is a threat to everyone who uses the New Forest.

Aren’t New Forest bendy roads dangerous?

+Most people do expect the bendy roads to be dangerous. You never can know what is around the next bend, whether a donkey or another animal, a walker, horse rider or cyclist.

On straight roads, however, we tend to be more confident. But grazing livestock are unpredictable. Anything can set them off. They move randomly from one grazing spot to another, with no road sense.

On straight roads, however, we tend to be more confident. But grazing livestock are unpredictable. Anything can set them off. They move randomly from one grazing spot to another, with no road sense.

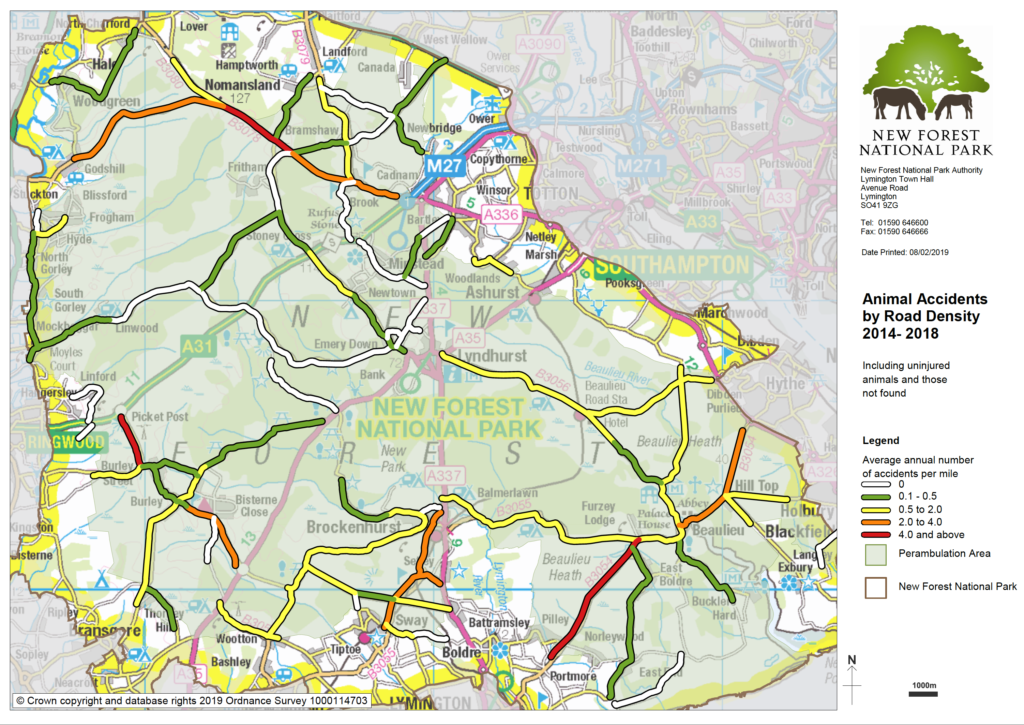

Mapping of accidents shows that the worst blackspots for animal accidents tend to be on perfectly straight roads. These are routes used daily by local drivers, particularly commuters.

In poor light oncoming traffic on these popular routes can make it hard to spot animals beside the road. Cars illegally parked on the verges makes this problem worse. Animals grazing quietly beside the road will move suddenly, stepping out into the traffic.

Animals will even choose to sleep on the warm road surface, and in winter will want to lick the salt spread by the gritters. In summer they will shade from the flies in dark patches under roadside trees, making them hard to spot in the contrasting light.

For all these reasons extra care is needed on the straight roads too. The best advice is to add a little time for any New Forest road journey. Adding just 3 minutes on even a 7 mile drive across the New Forest between the cattle grids, would allow you to drive around 30mph rather than stick to the usual 40mph limit. Hence the popular #Add3Minutes hashtag

The grazing animals are vital to the New Forest. Not just because they are an iconic part of its cultural heritage, but because their constant grazing keeps it very special for nature and accessible for everyone. We can all make our own contribution to keeping it special, for us, for the animals and their owners, and for nature.

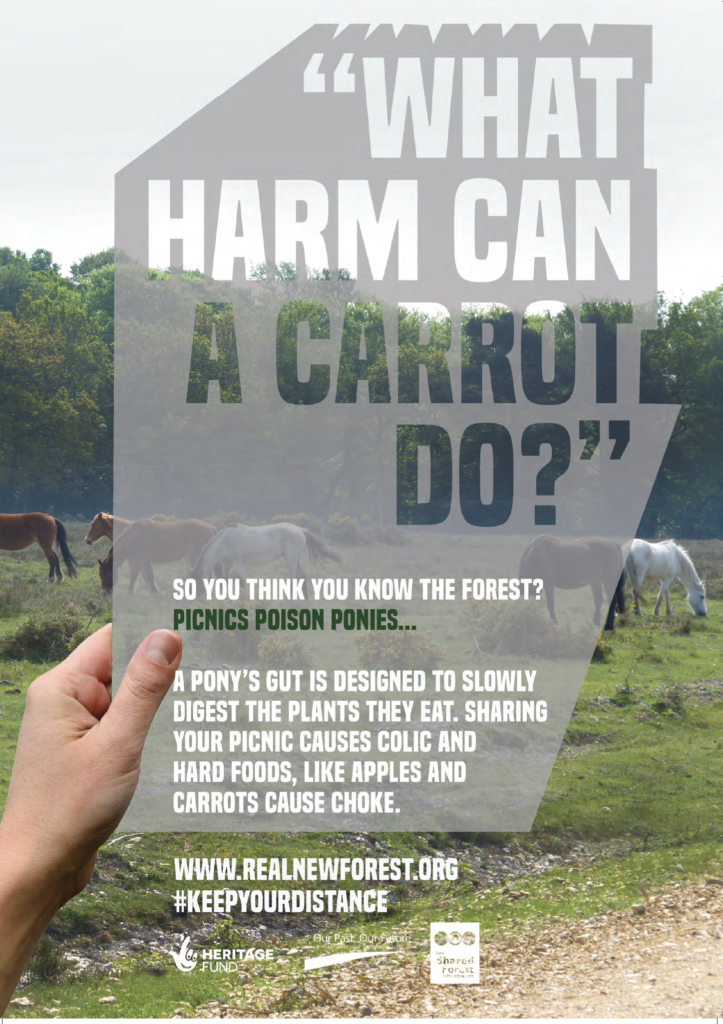

What harm can a carrot or apple do?

+ Not only is feeding commoners’ animals an offence under the byelaws, and antisocial as no-one welcomes strangers feeding their animals, but it is also very harmful. Contrary to common view carrots and apples are not safe for New Forest grazing livestock.

Not only is feeding commoners’ animals an offence under the byelaws, and antisocial as no-one welcomes strangers feeding their animals, but it is also very harmful. Contrary to common view carrots and apples are not safe for New Forest grazing livestock.

Anything in any quantity and any change in the normal diet can cause deadly colic. This is a very painful and is the most common cause of equine fatalities. In a domestic animal, under constant observation, treatment may be possible. For the semi-feral animals grazing the New Forest spotting the problem in time is unlikely.

Hard foods, like apples or carrots can cause choke. Equines have long, narrow guts and small stomachs. If a hard piece of feed gets stuck in its journey along the gut it causes a condition known as “choke”. The symptoms may emerge some time after eating the item. In the case of semi-feral New Forest ponies and donkeys it is unlikely that this will be spotted, and timely treatment provided. The build-up of fluid around an obstruction can also cause aspiration pneumonia.

Feeding disrupts healthy grazing habits. Ponies and donkeys are creatures of habit. They will quickly learn to hang around for treats if someone feeds them. When this does happen not only is it often beside New Forest roads, drawing them to danger, but it badly disrupts their grazing habits. The grazing livestock must be able to nourish themselves all year round, grazing for much of the day on the varied diet of what the New Forest offers naturally. Feeding leads to them waiting around in the hope of hand-feeding, they gradually lose condition, and are then unable to survive on the New Forest and have to be removed.

Feeding harms the grazed habitats. The New Forest is designated a National Park largely because of the continuously grazed habitats, upon which rare species depend. Feeding disrupts the natural movement of the livestock around the habitats, according to the weather conditions and vegetation growth.

Should we put water out for the animals in hot weather?

+No. There are natural water sources throughout the New Forest even in the most severe of droughts. They move naturally to the ponds, streams and valley mires in dry weather, and to the dry heaths in wet weather. This is good for them and good for the variety of habitats in the New Forest, ensuring that all are well-grazed at some point through the year. Unnatural sources also cause similar problems to illegal feeding, that commoners’ animals may congregate and become aggressive trying to drink at the same time. If the animals need any extra help then the owners will take them to their back-up grazing land.

Buckets etc., also heighten the risk of the spread of the strangles virus, which survives well in standing water.

Feeding of any sort, including placing water accessible to commoners’ livestock, is an offence under the Byelaws. Just follow the general rule of the Countryside Code and leave nothing but footprints.

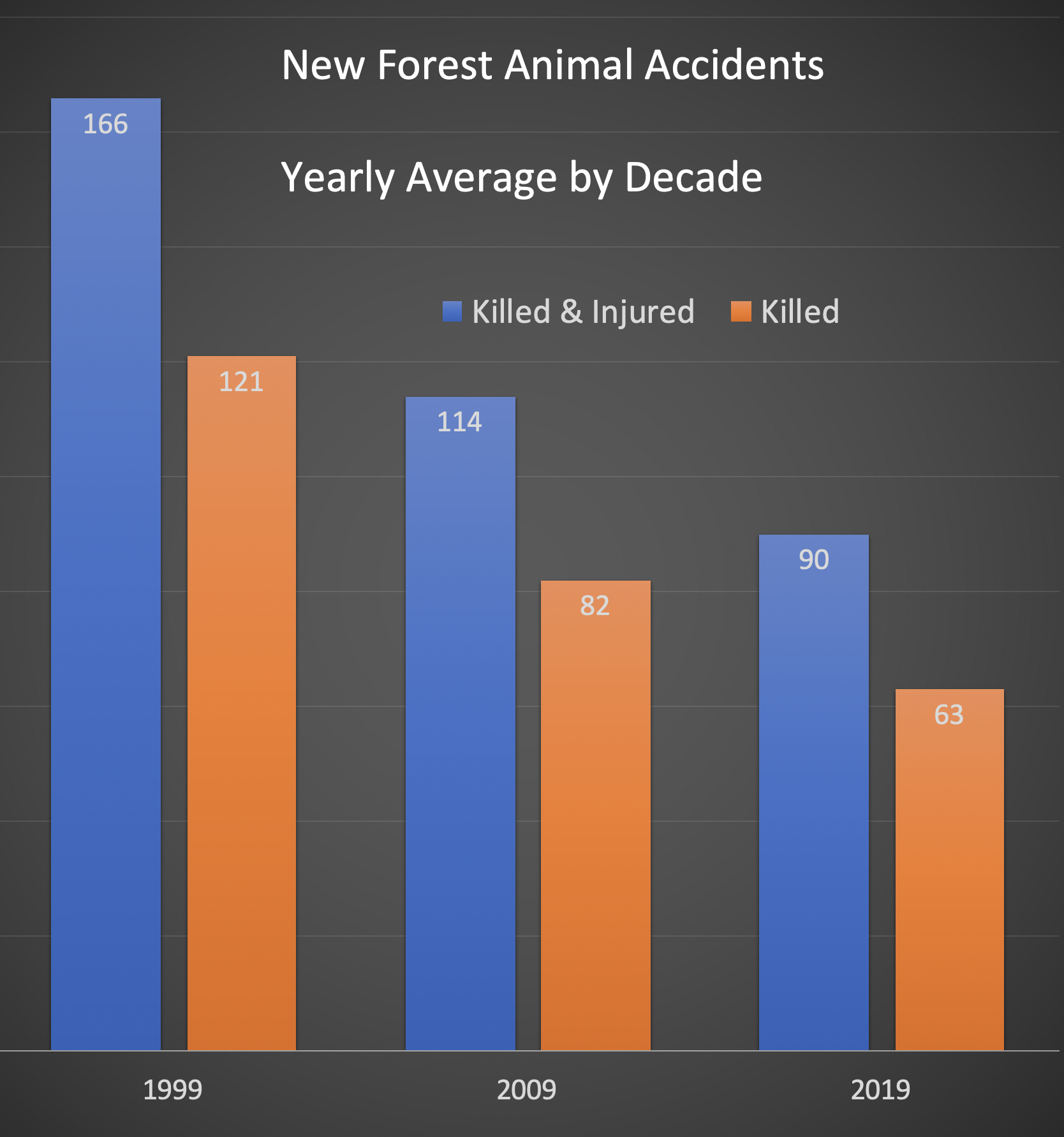

What are you doing to reduce animal accidents on the roads?

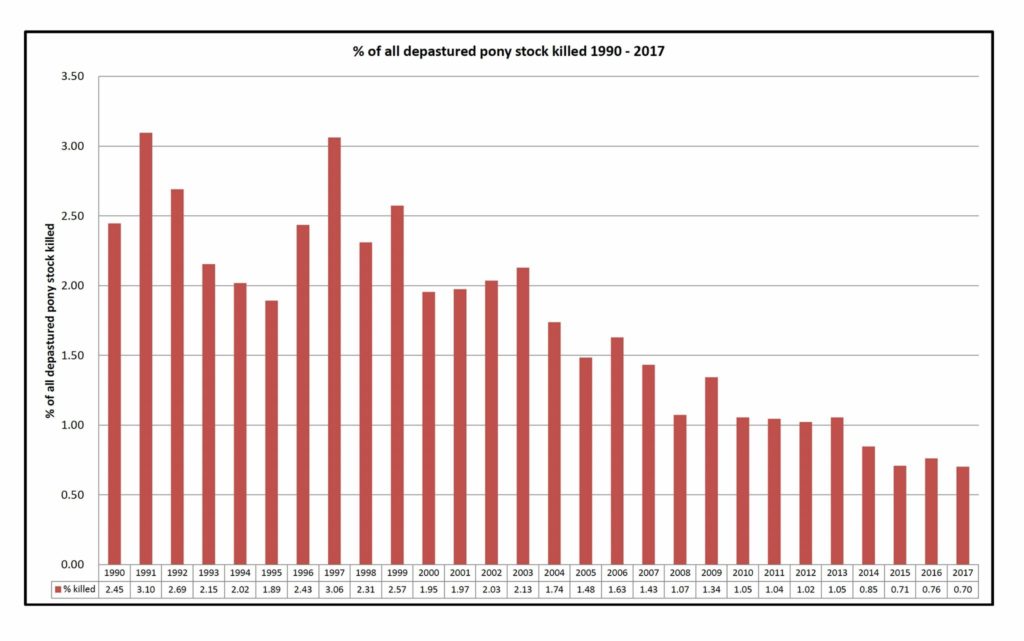

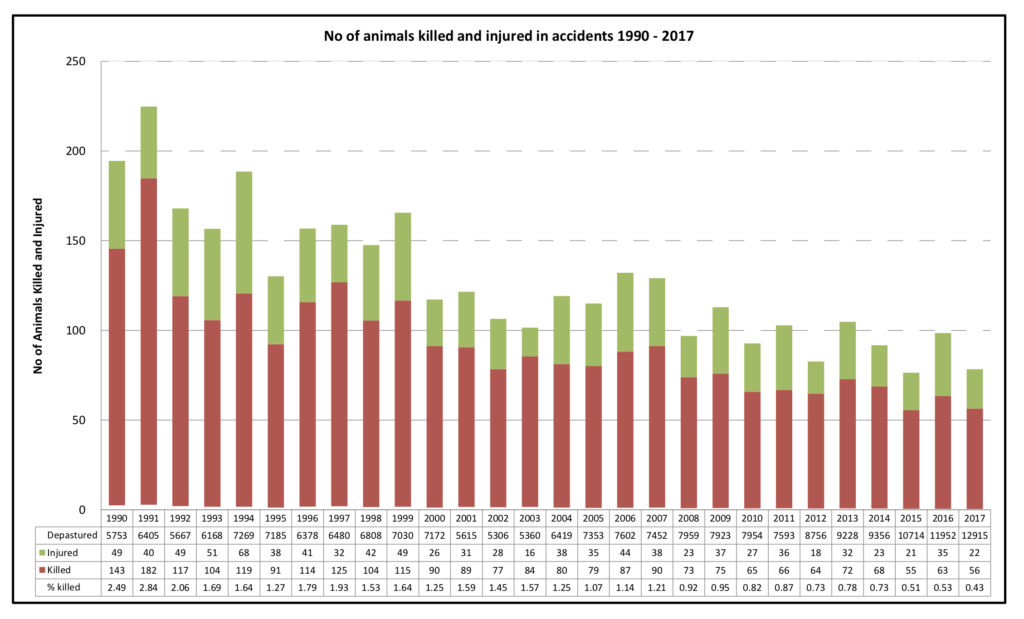

+ The number of animal accidents has reduced dramatically since the Verderers’ records began. We cannot know for sure the reasons why this has happened, but have been working with the other Forest organisations to keep up efforts to reduce the number of accidents. In fact the average number of animals killed each year has halved  since the 1990s. Despite the success in increasing the number of animals on the marking register to graze the New Forest, the proportion of those killed in accidents has fallen from 3% in some years in the 1990s to less than 1% today.

since the 1990s. Despite the success in increasing the number of animals on the marking register to graze the New Forest, the proportion of those killed in accidents has fallen from 3% in some years in the 1990s to less than 1% today.

Despite the real progress in reducing accidents it is important to understand that each one is a tragedy for the commoner concerned. Hit-and-run accidents are a particular concern due to the needless additional suffering caused. Failing to report an accident, leaving an animal in unnecessary suffering is an offence under the Animal Welfare Act. Failure to report any accident involving livestock is also an offence under the Road Traffic Act.

The CDA and Verderers have funded a reward scheme for information that leads to the prosecution of drivers who hit and run, which we increased to £5000 in 2017. This is a measure of how seriously we take these incidents.

The Verderers Higher Level Stewardship Scheme provides reflective collars suitable  for ponies and donkeys free of charge, which helps to ensure that those successfully caught by their owners or on drifts are fitted with a collar, and lost or dirty ones replaced each year. Because they are designed to be safe if they catch on anything this does mean that they get lost, but the numbers with collars at any point in time is increasing. Evidence suggests that these do help, although they cannot be a complete solution. In the end the avoidance of accidents requires driving that is appropriate to the conditions, including the presence of livestock on roads, their unpredictable behaviour and the level of visibility. In 2019 the Verderers began to make available reflective ear tags and reflective collars for cattle following successful trials.

for ponies and donkeys free of charge, which helps to ensure that those successfully caught by their owners or on drifts are fitted with a collar, and lost or dirty ones replaced each year. Because they are designed to be safe if they catch on anything this does mean that they get lost, but the numbers with collars at any point in time is increasing. Evidence suggests that these do help, although they cannot be a complete solution. In the end the avoidance of accidents requires driving that is appropriate to the conditions, including the presence of livestock on roads, their unpredictable behaviour and the level of visibility. In 2019 the Verderers began to make available reflective ear tags and reflective collars for cattle following successful trials.

Accidents peak around the evening commute and around the Autumn clock change, when more driving takes place in darkness. Our campaigns, therefore, concentrate on the Autumn, when we try to alert regular drivers to the higher risks they face. As everyone becomes oblivious to signs they see every day, we now have changing signage on the high risk routes and special signs for the winter. In 2018 Hampshire County Council made these winter signs reflective, following the first experiment in 2017.

The biggest change is that all local agencies and organisations are now working around concerted campaigns and highlighting how little effort is involved in driving appropriately: The thinking behind the #Add3Minutes hashtag – the small amount of extra time added to a 7 mile journey across the Forest by driving at 30mph instead of the usual 40mph speed limit.

The biggest change is that all local agencies and organisations are now working around concerted campaigns and highlighting how little effort is involved in driving appropriately: The thinking behind the #Add3Minutes hashtag – the small amount of extra time added to a 7 mile journey across the Forest by driving at 30mph instead of the usual 40mph speed limit.

Since 2011 the CDA has also been pushing for improved signage at access points, and in 2018 Hampshire has extended the use of the surface-painted “running pony” warning triangle to busiest access points at the cattle grids. Hopefully the combination of the unusual signage and the rattle of the grid will remind drivers that they are entering a special landscape requiring special attention.

There will always be people for whom enforcement is the only deterrent. We are pleased that the Verderers have been working with Hampshire police, giving financial support to the speed enforcement van, which now works in daylight and darkness. The CDA is also involved with work on the feasibility of the deployment of average speed cameras on one of the high risk routes, and are now hopeful that funding will become available to prioritise this initiative.

Along with the Verderers we have long supported a general speed limit of 30mph throughout the Forest, and not just in the villages as at present. In 2018 we also lobbied for the volunteer Community Speedwatch teams to operate on the 40mph, because Hampshire Constabulary had restricted them to the 30mph roads, thus preventing this valuable work happening on most of the open Forest roads. Data from the Sway team shows a dramatic increase in the proportion of drivers on Pitmore Lane (A 30mph limit road on the Open Forest) driving more slowly since the team began its work. Today around 7 in 10 drivers are travelling at a sensible speed, compared to less than half when the team first recorded speeds. Thankfully, the Police agreed in March 2018 that the 40mph routes could be covered by Speedwatch subject to finding safe locations for volunteers to do this reminding drivers of the need to drive with special care on the Forest. You can find out more about volunteering for one of the groups, or forming a new one, here

Contrary to popular myth most accidents occur on the 40mph routes heavily used by commuters, where the roads are straight and sightlines are good across open countryside. This is shown by the map of accidents where the highest risk routes are shown in red and orange. Anyone familiar with reports of accidents will recall the most common spots for accidents, on straight roads where drivers are particularly confident in their safety.

Thank You

Commoners are very grateful to all those individuals and organisations who are working with us, and welcome new ideas for ways of helping people drive with special care in the New Forest, where grazing animals have right of way on the roads, and whose constant and widespread grazing is essential to keeping the New Forest so special and loved by millions.

Find out more

More data on animal accidents are available on the National Park Authority website – A couple are reproduced here.

We also have a leaflet offering practical advice to New Forest drivers.

Why don’t all animals have reflective collars?

+Collars help significantly with keeping commoners’ animals safe on New Forest road, and are probably one of the reasons for the improvement in the rate of accidents over the past two decades. Collars have been designed to be safe for ponies, so they can’t get strangled by them, but the elastic content means that they are quite easily removed. The owners will do their best to replace them when they can, but often this can only be done when they are rounded-up and in the Autumn, which also depends upon them being caught by a round-up.

Collars cannot be safely fitted to foals, and we’ve not found one that is effective for cows, sheep or pigs. In 2018 commoners did start experimenting with reflective ear tags for cattle.

It is important to remember that collars do not show up from all directions, and are not an alternative to taking very special care on New Forest roads. The animals have right of way on New Forest roads, and it is important that they use them to move between grazing areas.

I’ve seen a dog chasing a pony. What should I do?

+Call the Police. Please note as much information as possible on the dog, its owner and any vehicle, and the animal being chased.

Worrying livestock on grazing land is a criminal offence under the Dogs (Protection of Livestock) Act 1953. Worrying includes chasing or attacking an animal, whether it is a sheep, cow or pony. The court can order for the dog to be destroyed, for the dog to be muzzled or kept on a lead, and for the owner to be fine and forced to pay compensation to the livestock owner.

Since 2014 it has is been a criminal offence for a dog to be “out of control” in a public place under the amended Dangerous Dogs Act 1991. They can be prosecuted not only if the dog actually injures someone or makes them worried about being injured, but also if it attacks someone’s animal or makes the owner worried about the risks of trying to stop an attack on their own animal.

In the New Forest we also benefit from specific byelaws under which dog owners can be prosecuted. On the Crown Lands managed by the Forestry Commission the byelaws make it an offence for any dog to be out of control, giving its staff the power to demand that a dog is put on a lead. The National Trust byelaws prohibit any dog that is not under “proper control” and annoying or disturbing any person or animal.

Do the RSPCA or other welfare organisations inspect the animals?

+There are two welfare tours each year arranged by the Verderers. They are attended by DEFRA, British Horse Society, International League for the Protection of Horses, Blue Cross, RSPCA, Donkey Sanctuary, and local veterinary surgeons. The results of the survey are reported in the minutes of the Verderers’ Court. The welfare organisations also carry out their own independent inspections.

Why isn’t the New Forest pony the only breed on the Forest?

+

Commoners have the right to turn out any unshod equine to graze the New Forest. The only exception is that it must not be an entire male. It does not need to be a pure-bred New Forest Pony. Each commoner is responsible for their own animals, and is free to decide what is best for them and for their animal’s welfare. Some breeds will be less hardy than a New Forest pony, and some as hardy. Whatever the breed they will have to be taken home if and when they need additional care. Donkeys too have a very long history in the New Forest. You will see donkeys, shetlands and coloured ponies grazing the New Forest during the year, and being sold at the Beaulieu Road sale-yard. Every equine mouth helps maintain the habitats of the New Forest through their grazing, and each breed grazes a little differently. It all helps.

Each commoner will have their own plans for their Forest-run ponies, some will stay to graze the Forest, some will become their own riding, driving or showing ponies, and some will be sold to new owners. This is a genuine case of “horses for courses”. A little variation in the animals that graze the Forest is simply a reflection of the diversity within commoning.

Of course, the New Forest pony is the best adapted to grazing the extraordinary mosaic of habitats, ranging from coastal marshes and bogs, to dry heaths, hedgerows and woodlands. Breeding has been carefully managed to ensure that the qualities of the New Forest pony are maintained, particularly through the selection and control of stallions; they are all pure-bred, pedigree New Forest, rigorously inspected and licensed. Stallion numbers on the New Forest are adjusted each year according to market conditions for the sales. The New Forest Pony is now included on the list of native rare breeds. Since the 1980s the commoners have instigated successive schemes to encourage the keeping of high quality registered New Forest mares.

Most foals bred on the New Forest are registered with the Breed Society, whether as pure-bred or cross-bred. Around 9 in 10 of the foals registered each year by the Breed Society are pure-bred New Forest ponies*. Of course, any Shetlands and Exmoors etc., are registered with their respective societies instead of ours. All foals must be registered and “Forest-bred” remains a very desirable attribute, and is controlled by the Society. The first volume of the New Forest Pony Stud Book was published in 1910.

There are several pieces of folklore around the development of today’s New Forest pony breed. In her wonderful book “New Forest Ponies” Dionis Macnair says:

“Every native breed has the myth of the stallion that swam ashore from the Armada – certainly not possible in the New Forest; there were no wrecks in the South Coast. As we know there was a Royal Stud in the Forest it seems very probable Spanish stallions stood here and were crossed with the local ponies to breed these more athletic mounts. This would be the first chance to try them in action. We also have stories of veteran army horses turned out on the Forest”

For more on the story of the New Forest Pony take a look at the Breed Society website

*In 2018 there were 15 selected stallions turned out for up to 37 days; this was the highest number and length of time for some years. As a result, In 2019 the Breed Society registered 413 foals, of which 373 (90%) were pure-bred New Forest ponies.

Managing the New Forest

+Why is it OK for horses to be ridden over the New Forest, but not bikes?

+Horses and ponies are central to the special qualities of the New Forest.

Access on horseback is written into New Forest law. It is an ancient and important part of New Forest culture. This is primarily because there is no better way for commoners to check their livestock; they are much easier to spot from horseback than from any other means of travel, seeing over the gorse bushes, and a horse can go anywhere that a pony or cow might go. The riding culture of the New Forest and the benefits of using horses means that there is much less use of 4x4s or quad-bikes than is seen elsewhere on common land.

Riding ponies are an important product of the commoning system upon which the New Forest depends. Commoners will often themselves ride ponies that they been born and bred on the Open Forest, and later sell these experienced ponies on to the general public. Riding them on the Forest gets them used to a range of situations that makes them exceptional. Horses raised elsewhere are likely to be terrified of traffic, pigs, donkeys, cattle, and many of the human recreational activities seen on the Forest.

Commoners derive important support from local riding; as a market for hay, farriery, saddlery, and horse liveries, for example. Local riding also supports the suppliers upon which commoners also depend; feed merchants, large animal veterinary practices, animal rescue services, and the New Forest Hounds’ vital service rapidly collecting livestock that die on the Open Forest.

The action of horse and pony hooves on the ground, and dung, is part of the ecosystem of the New Forest, which is neither ploughed nor artificially fertilised. Many of the species that still exist today in the New Forest but which are rare elsewhere, continue to depend on these long-standing ground effects of livestock, particularly soil poaching.

In the 1990s rights of access were extended to bicycles on many of the gravelled tracks, in the hope that this would prevent unlawful access across more sensitive terrain. There are, perhaps, three main reasons why more extensive cycle access would be a cause for concern.

Firstly, far more people have access to a bicycle than ride, so the potential impact on the special qualities of the New Forest is substantial.

Secondly, the action of a wheel (whether a car or a bike) can very quickly create artificial new channels for water erosion and rapid run-off.

Finally, the potential speed of a cycle downhill can present a real danger to other Forest users (particularly on horseback), and startling for commoners’ livestock. A startled pony will put itself (and others) in danger of injury when in flight after being startled.

None of this means that horse riding does not cause concern of course. Any activity can be done sensitively or badly. In the past, when there were commercial riding stables dotted all over the Forest, some tracks were used multiple times a day every day, causing considerable erosion. Today, the very few that remain are licensed, with very clear terms to avoid damage. Riders are not permitted to build jumps, and they are required to be considerate to other users and to the rare species of the New Forest. Large events have to be licensed and conditions on routes etc., respected.

Shouldn’t the New Forest be rewilded?

+The landscape of the New Forest is one of the few places where traditional, pastoral land management has survived. Because of this it still supports numerous rare species that were once common across the UK. The environmental success of the area is achieved by striking a careful balance between maintaining its wild character and sensitive land management, including rotational cutting and burning and, of course, constant grazing by herbivores. Places are reported to have ‘rewilded” have, in fact, adopted systems of grazing and land management similar to those long practiced in the New Forest.

Is the New Forest overgrazed?

+

Shirley Holms – January 2019

Many people falsely interpret the Verderers’ Marking Register as a record of the number of animals actually grazing the Forest. The reality is much more complex, as many of these animals may only briefly, occasionally, or never be turned out to graze.

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) Basic Payments Scheme (BPS), for example, requires farmers to present the marking fee receipt in order to qualify for basic payment on the animal. It would not make sense to require that these are turned out. It is more important that commoners, the Verderers, and Natural England assess conditions on a local, case by case basis with the welfare of the livestock and the biodiversity of the New Forest uppermost in their decisions. It is unfortunate that the Common Agricultural Policy works in a way that causes this confusion, and the Commoners Defence Association has been working closely with the other major New Forest organisations to lobby for a future support system that is better suited to the unique circumstances of the New Forest. The Basic Payment Scheme has given an important boost to commoning, which was in a very poor state previously, enabling commoners to invest in their holdings, the welfare of their herds, and to achieve the increase in cattle numbers required by Natural England. Despite BPS support, however, commoners must still subsidise their commitment to Forest grazing with income from their “day” jobs, and with their time.

The Marking Register situation was made worse when the Government announced that payments during the years of the transition by the BPS would be based upon a Reference Period, without declaring which years’ payments would be used. This strengthened the perverse incentive to mark additional animals in case the current year becomes the basis for several years of payments. If and when the Reference Period is declared the link between the number of animals marked and the payment will be broken. At that point we may have an indication of the true commitment to commoning, given that BPS receipts will have no link to New Forest activity. In February 2020 we wrote to the Secretary of State calling for an early decision. Our local MPs, the National Park Authority, the Verderers, and Forestry England all supported our lobby for an early decision.

Commoners have a very strong interest in protecting the New Forest. Indeed, we are usually the first to act when damage is done to the habitats that our animals graze. The grass, shrubs, hedges, water sources and trees are all vital to the welfare of our livestock.

As commoners we must judge grazing levels by the condition of our livestock, sustained by what the New Forest provides, and the condition of the habitats supported by grazing. Twice a year the Verderers run a welfare tour, taking national and local organisations with an interest in welfare to random sites to inspect the livestock. Commoners have an individual responsibility for the condition of their animals, and will take them home should they lose condition with no early prospect of improvement. Natural England have responsibility for the condition of the habitats, which are broken down into individual SSSI units. Natural England assesses that of the 29,000 hectares in the New Forest SSSI just 1.14% are unfavourable and declining. The majority of the 582 SSSI units are in favourable condition some 97% either favourable or unfavourable and recovering. Anyone who takes a moment to study the Natural England assessments will soon discover common reasons amongst those few SSSI units in declining condition, particularly undergrazing, human interference with watercourses, campsite and other human pressures. The most recent assessments also show the benefits of some of the work that has been done under our current agri-environment scheme (known as Pillar II of the Common Agricultural Policy).

The Verderers Higher Level Stewardship Scheme (HLS) for 2010-2020 and its predecessor schemes have played a significant part in this exceptional achievement. The current Verderers HLS Agreement also includes specific conditions for each habitat type, for example ensuring that there is sufficient soil poaching by cattle to sustain some of the rare breads that survive in the New Forest, of which the small fleabane is the most cited example given that it has declined catastrophically from being widespread across Britain to near extinction other than its New Forest strongholds. The HLS required the partners to ensure that the proportion of cattle in the Forest’s stock was increased in order to maximise the biodiversity potential from grazing.

The New Forest pony too is now a rare breed and it is vital that pony numbers are kept at levels that provide sufficient foals to maintain disappearing bloodlines.

In 2020, following CDA representations on the marking register, Julian Lewis MP asked ministers for a statement on New Forest grazing levels. On 11th May the agriculture minister, Victoria Prentis MP, responded:

Natural England recently recommended that the Environmental Stewardship Higher Level agreement with the Verderers should be extended by one year as the agreement was delivering its objectives and the Sites of Special Scientific Interest within the forest were being managed in a way that improved their condition. We are not aware of damage to landscape due to increased numbers of de-pastured cattle.

Why isn’t the New Forest pony the only breed on the Forest?

+

Commoners have the right to turn out any unshod equine to graze the New Forest. The only exception is that it must not be an entire male. It does not need to be a pure-bred New Forest Pony. Each commoner is responsible for their own animals, and is free to decide what is best for them and for their animal’s welfare. Some breeds will be less hardy than a New Forest pony, and some as hardy. Whatever the breed they will have to be taken home if and when they need additional care. Donkeys too have a very long history in the New Forest. You will see donkeys, shetlands and coloured ponies grazing the New Forest during the year, and being sold at the Beaulieu Road sale-yard. Every equine mouth helps maintain the habitats of the New Forest through their grazing, and each breed grazes a little differently. It all helps.

Each commoner will have their own plans for their Forest-run ponies, some will stay to graze the Forest, some will become their own riding, driving or showing ponies, and some will be sold to new owners. This is a genuine case of “horses for courses”. A little variation in the animals that graze the Forest is simply a reflection of the diversity within commoning.

Of course, the New Forest pony is the best adapted to grazing the extraordinary mosaic of habitats, ranging from coastal marshes and bogs, to dry heaths, hedgerows and woodlands. Breeding has been carefully managed to ensure that the qualities of the New Forest pony are maintained, particularly through the selection and control of stallions; they are all pure-bred, pedigree New Forest, rigorously inspected and licensed. Stallion numbers on the New Forest are adjusted each year according to market conditions for the sales. The New Forest Pony is now included on the list of native rare breeds. Since the 1980s the commoners have instigated successive schemes to encourage the keeping of high quality registered New Forest mares.

Most foals bred on the New Forest are registered with the Breed Society, whether as pure-bred or cross-bred. Around 9 in 10 of the foals registered each year by the Breed Society are pure-bred New Forest ponies*. Of course, any Shetlands and Exmoors etc., are registered with their respective societies instead of ours. All foals must be registered and “Forest-bred” remains a very desirable attribute, and is controlled by the Society. The first volume of the New Forest Pony Stud Book was published in 1910.

There are several pieces of folklore around the development of today’s New Forest pony breed. In her wonderful book “New Forest Ponies” Dionis Macnair says:

“Every native breed has the myth of the stallion that swam ashore from the Armada – certainly not possible in the New Forest; there were no wrecks in the South Coast. As we know there was a Royal Stud in the Forest it seems very probable Spanish stallions stood here and were crossed with the local ponies to breed these more athletic mounts. This would be the first chance to try them in action. We also have stories of veteran army horses turned out on the Forest”

For more on the story of the New Forest Pony take a look at the Breed Society website

*In 2018 there were 15 selected stallions turned out for up to 37 days; this was the highest number and length of time for some years. As a result, In 2019 the Breed Society registered 413 foals, of which 373 (90%) were pure-bred New Forest ponies.

How are commoners represented in the Verderers Court?

+Anyone, commoner or not, can make a “presentment” to the regular meetings of the Verderers Court on any Forest matter than concerns them. The commoners also elect their five members of the Verderers Court, to represent them within this important decision making body, and sit alongside the four appointed verderers, and the Official Verderer. The Official Verderer is usually also a commoner. The Verderers’ website provides useful information on the Court and the work of the Verderers.

What happens when an animal dies?

+Whether a commoner’s animal dies naturally or in an accident the New Forest relies on the local hunt to collect and dispose of the remains so they are not left on the Forest. Thankfully the New Forest Hounds do this quickly and efficiently. The huntsman is certainly one of the many unsung heroes of the New Forest, as this is an important but rather thankless task. The Verderers Higher Level Stewardship Scheme has supported the hunt to meet the rising costs of incineration, so the system meets the latest environmental standards.

How is the Boxing Day Point-to-Point good for the New Forest?

+

The annual point to point is the year’s most important social gathering for commoning, serving multiple purposes beneficial to the New Forest.

The Point to Point:

- Is a showcase for the extraordinary abilities of the rare breed New Forest Pony, hence the restricted races and prizes for registered New Forest ponies, and New Forest first-cross and part-bred horses.

- Provides a strong incentive for commoners to help on horseback in the essential autumn round-ups, known as “drifts”. The drifts are vital to the management of the grazing ponies, and volunteer riders are crucial to assist the agisters. Riders build knowledge of the terrain away from their local haunts, and their riding ponies get used to working at speed in company – important attributes for riding the point to point.

- Brings together the commoning community, to chat, to show off their ponies, their commoning skills, and to have fun. This is the only occasion in the year that brings together most commoners. The sense of community, and the focal point, is an important draw for young commoners to remain involved in commoning amidst increasingly busy lives at school, college or work.

- A point to point, testing the Forest knowledge and riding skills of commoners has been ru as a formal event for more than 100 years. It is an important and popular demonstration of the unique cultural heritage of the New Forest as a surviving unenclosed landscape.

- Is run by the local charity, the New Forest Pony Breeding and Cattle Society (Charity No. 1064746). Any proceeds from the event are used to support the important work of the charity.

The extraordinary biodiversity and cultural heritage of the New Forest depend upon the continuation of the vocational system of livestock grazing. It is a vocation that is increasingly demanding, in both time and money.

The event itself is very carefully managed to minimise its impact on the landscape, under terms agreed with Forestry England. It takes place outside the growing and nesting seasons, with careful consideration and months of preparation given to the finish location, for vehicular access and parking. Because of this none of the finish sites have ever experienced any lasting impact from the event.

Commoners care deeply about the New Forest, and are particularly careful not to damage the grazing upon which their animals depend, nor to leave anything behind. The effort put in to the annual point to point ensures that it continues to make a very positive contribution to this very special landscape. The biggest risk of harm to the New Forest is the decline of vocational commoning amidst the pressures of modern life – The Point to Point is of huge value in encouraging local people to maintain their commitment to grazing animals on the landscape, with a real sense of identity and community.

Do commoners have to pay to graze animals on the Forest?

+Marking fees are payments made on each animal turned out onto the Forest for the present year. They are set by the Verderers and help towards the agisters’ (q.v.) salaries. No animal over 6 months age is allowed to be turned out on the Forest before the marking fee is paid and the animal marked by the agister.

Insurance for Commoners

+I am claiming BPS, should I have my own insurance?

+Answer Many commoners do not see themselves as running a ‘business’, however by accepting Government/EU agricultural subsidies and payments, selling through commercial sale yards, taking part in mass ‘stud’ activities, running and advertising studs and stock for sale, occupying land under farm business tenancies’ which are all likely to be classed in some (including insurers, and possibly HMRC) eyes as an ‘economic activity’, this could therefore mean it is classed as a business (even if it is small and unprofitable!). This would also mean that all the private insurance cover often given as part of a membership of an organisation (eg BHS, CA, BASC etc) may not cover these types of economic activity’ as they are considered purely domestic (ie, they are designed for: we have a horse, we keep it in a field or livery yard and we ride it after work, and go to shows at the weekend).

It should also be noted that anyone claiming BPS from the forest allocation, tick a box in the sign-up process to declare ‘I am an active farmer’ as only active farmers are eligible for BPS payments.

There are several insurance providers who provide smallholder and farm policies that include commoning as part of their covered activities and so the majority of commoners really should have a policy in their own right in this day and age.

I’ve volunteered to help on the NFCDA stand at the New Forest Show and to take out the mobile exhibition. Am I covered by the NFCDA insurance in the event of an accident?

+The NFCDA policy through the NFU Mutual covers our members for these types of volunteer activities.

I’m taking my stallion to the pony breeders annual stallion show and my mare, does the NFCDA insurance cover me when I’m in transit and on site?

+No. The NFCDA insurance policy does NOT cover anything other than while your animal is on the crown lands / adjacent commons. We would advise you to obtain your own insurance for this activity.

I’m attending a drift (walker or rider). Does the NFCDA insurance cover me for any Incidents?

+No. The Verderers’ have responsibility for volunteers operating at a drift.

If I’m out in the forest trying to catch a mare and foal, or my cows, and there is an incident with a walker which requires medical attention, does then NFCDA insurance policy cover me?

+No. The NFCDA insurance policy does NOT cover anything other than while your animal is on the crown lands / adjacent commons. We would advise you to obtain your own insurance for this activity.

I’m taking a pony to sell at Beaulieu Road; does the NFCDA insurance cover me when in transit, unloading or loading at Beaulieu Road?

+No. The NFCDA insurance policy does NOT cover anything other than while your animal is on the crown lands / adjacent commons. We would advise you to obtain your own insurance for this activity.

If I have a stallion in the stallion scheme and they are in the dedicated grazing (Cadlands, New Park) does the NFCDA cover me for any incidents?

+No. The NFCDA insurance policy does NOT cover anything other than while your animal is on the crown lands / adjacent commons. To be part of the stallion scheme, when you sign up you have to have your own liability insurance of at least £5m.

If I bring my ponies in off the forest and they jump into a next door neighbour’s field, and there is an incident such as injury to my neighbour’s animals, or an injury to my neighbour, does the NFCDA insurance cover it?

+No. The NFCDA insurance policy does NOT cover anything other than while your animal is on the crown lands / adjacent commons. We would advise you to obtain your own insurance for this activity.

If my cattle come in for TB testing and there is an incident such as injury to a person using cattle crush does the NFCDA insurance cover me?

+No. The NFCDA insurance policy does NOT cover anything other than whilst your animal is on the crown lands / adjacent commons. We would advise you to obtain your own insurance for this activity.

Does the NFCDA insurance cover me for public liability if there is an incident on the open forest such as my pony or cow kicks or bites a forest user?

+Yes. The NFCDA policy through the the NFU Mutual covers our members’ liability for stock lawfully depastured on the crown lands / adjacent commons, but only if you do not have your own more specific policy covering the same loss.

Members Login

Latest Tweets

Latest Tweets

Follow us

@realnewforest 4h

Icilibus sam quas aut eriatem nume corepta auta conet officaborem quodi corepta auta conet officaborem quodi apernat ectlpa dolorpiaecus.

@realnewforest 4h

Icilibus sam quas aut eriatem nume corepta auta conet officaborem quodi corepta auta conet officaborem quodi apernat ectlpa dolorpiaecus.

@realnewforest 4h

Icilibus sam quas aut eriatem nume corepta auta conet officaborem quodi corepta auta conet officaborem quodi apernat ectlpa dolorpiaecus.

With thanks for support from