Tony Hockley, CDA Chair

27th February 2020

The Government has now offered more clues regarding post-Brexit agricultural and environmental policies. These will be made possible by legislation now making  its way through parliament. The February 2020 farming policy update and a discussion paper on future environmental land management give some cause for hope in terms of continued investment in the New Forest; perhaps even a degree of quiet confidence that the local partnership work of recent years could continue to develop and grow under a new system. As ever in times of change,

its way through parliament. The February 2020 farming policy update and a discussion paper on future environmental land management give some cause for hope in terms of continued investment in the New Forest; perhaps even a degree of quiet confidence that the local partnership work of recent years could continue to develop and grow under a new system. As ever in times of change,  however, the transition from one system to another also brings very real risks. The biggest of these risks could be reduced quite easily, but it seems hard to get the New Forest voice heard in Whitehall. The dither and delay on the fate of the Verderers HLS does not inspire confidence in decision-making, and suggests we will need to shout more loudly, and much more early.

however, the transition from one system to another also brings very real risks. The biggest of these risks could be reduced quite easily, but it seems hard to get the New Forest voice heard in Whitehall. The dither and delay on the fate of the Verderers HLS does not inspire confidence in decision-making, and suggests we will need to shout more loudly, and much more early.

Dither & Delay: Decision on the Verderers HLS

Exactly one month before the expiry of the Verderers Higher Level Stewardship (HLS) scheme, the Rural Payments Agency finally agreed that this 10-year scheme would roll forward for a year from its February end date, as had happened in 2019 for the National Trust commons HLS. The roll-forward for the Crown lands of the New Forest could now last for up to four years, but decided annually. This may provide a bit of a cushion against the inevitable risks involved in the phase-out of the Basic Payments Scheme support from 2021, affecting many commoners. Nevertheless, several other landholdings in the open Forest have seen their HLS schemes come to an end, so that they are no longer within any form of “environmental stewardship”. The long delay to confirmation has had real impact; key staff from the incredible projects funded by the HLS have been lost due to the uncertainty over their roles, and the challenge of recruiting new expert staff with only short-term funding will be significant. The wetland and heathland restoration projects, and the New Forest Land Advice Service require real, local expertise if they are to continue at their previous pace.

The delay to confirmation of the HLS really was inexcusable given all that has been achieved by the Verderers HLS. This is the biggest agri-environment scheme in England, and one of the most innovative. Lowland heath is one of the rarest habitats in the world, more rare than rainforest, and still being lost. The New Forest is a prime, surviving example. The HLS has enabled parts of the open Forest that were lost to Forestry Commission conifer planting in the 20th Century, to be restored as fantastic grazed habitats, with incredible biodiversity and huge carbon storage capacity. If the Government is looking for an existing demonstration site for the Government’s ambition of using “public money for public goods”, then the Verderers HLS would be a leading candidate. That the HLS came within 30 days of ending with no viable alternative to replace it was simply ridiculous.

The Verderers HLS also supports a “Grazing Scheme”, offering practical support to New Forest commoning. Direct financial support is tailored to local priorities, with a fixed cap on the amount that can be received by any commoner, giving the greatest support where it is need to mitigate the additional costs of cattle-keeping, along with the provision of a few carefully-targeted cattle “feeding areas” to support cattle herds. It has also helped bring down the number of animals lost to traffic on the roads by providing thousands of reflective collars for ponies and cattle. That all of this can now continue whilst a new system of financial support is devised and introduced is a considerable relief.

Phasing out the Basic Payments Scheme

Anyone familiar with the governance of the New Forest will know that the CAP Basic Payment Scheme is something of a blunt instrument, ill-suited to the needs of this unique landscape. Nevertheless, it has played a vital role in sustaining cattle grazing in particular, following a period in which there was widespread concern that cattle commoning was dying out; threatening the many rare species that depend upon it. The BPS years have enabled commoners to invest in their back-up land and facilities, despite living in Britain’s least affordable national park, and despite the lure of profitable alternative uses of enclosed land within a very popular national park.

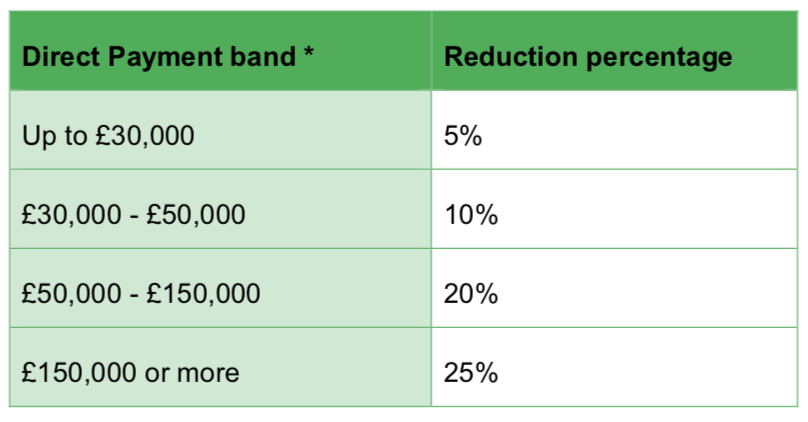

Proposed BPS reductions in 2021

Government policy is that BPS support will gradually be phased out from 2021 to 2027, to be replaced from 2024 by new Environmental Land Management Schemes (ELMS). In the interim new approaches will be tested, funded by the BPS reductions. The policy is that those who receive the most will be first in line for significant cuts to BPS. At present only the year one reductions have been announced. This process does mean that the financial impact on New Forest commoning may not be seen for several years, as the majority of commoners who do claim support under the BPS are at the bottom end of the scale, so will face small initial reductions in the amount they receive for their commoning commitments. Of course, most commoners already subsidise their communing from their day jobs, so that reliance upon the BPS within household income will often be lower than for farmers elsewhere: In this regard New Forest commoning is probably already one of the most diversified farming activities, supported (out of necessity) by multiple income sources and a large “leisure” time commitment.

The end of “mapping”

Some of the practical impact of change, however, will come very soon. From 2021 BPS payments will be “delinked” from the eligible land. This will finally end the nonsense of mapping the “eligible area”; a daft process which, for example, excludes areas of gorse from the grazing land. Gorse is an important habitat on lowland heath and valuable fodder for commoners’ animals. Following this “delinking” the hypothetical amount from which transition payments will be calculated will be based on a “reference period”. The sooner the reference year is set, the better. Knowing that there will be a “reference period” but not knowing what year or years it will be just creates a powerful perverse incentive to maximise the number of animals marked. For the New Forest this creates a huge workload for the agisters, marking animals that will never graze the New Forest. This undermines the credibility of the marking register as a record of grazing levels and the health of the commoning system. With a fixed pot of funding for the eligible New Forest area, this inflationary effect simply punishes responsible commoners: As the number of animals marked increases, the amount received per animal falls. This prospect is made even worse by the suggestion that the amount due for the entirety of the transition years could be taken as a single lump-sum. The perverse incentive in this situation is huge. In this time of uncertainty we will need to sustain the responsible, committed commoners who will stick with the practice whatever comes next, not those who will take the money and run. Even worse some current BPS claimants using New Forest entitlements may take the money pot and and also take the scarce back-up land that they use out of commoning, perhaps putting it to lucrative recreational use. The scarcity of back-up land has long been a practical threat to the continuation of commoning. Every animal turned out to graze must have someone to be kept if and when it is taken off the open Forest.

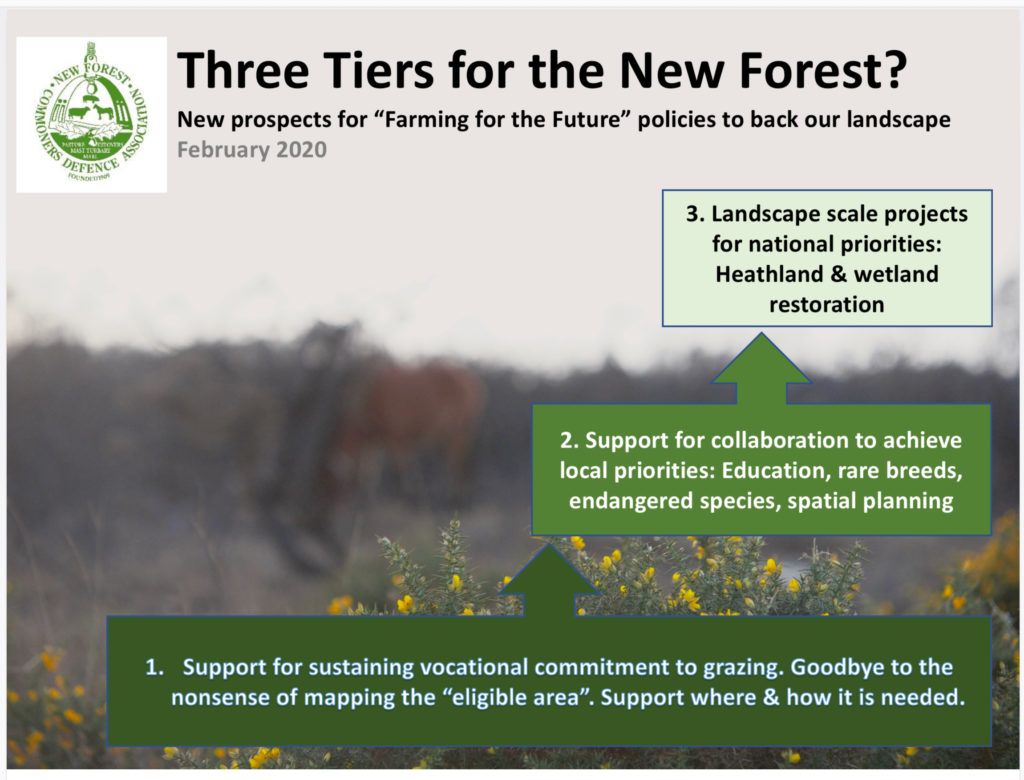

The Future: One scheme, three tiers?

Once the immediate risks of the transition are dealt with then our attention can turn to the new scheme. DEFRA are suggesting three tiers. The diversity of the New Forest, and the breadth of the public goods it offers, seems to suggest that all three tiers should apply.

Tier one- Encouraging environmentally sustainable farming. This seems the obvious basis for core but conditional support for good commoning practice, similar in some ways to the Verderers Grazing Scheme; backing high standards of animal and land management, delivering multiple public goods on the Forest and on commoners’ back-up land. As for upland commoners, it will be vital that individual commoners receive directly support for the valuable work they do, and the considerable pressures they must withstand.

Tier two – Delivering locally-targeted environmental outcomes. This could follow on from much of the species and habitat-specific collaborative project work that has taken place under the various HLS schemes and within the National Lottery Heritage Fund landscape partnership “Our Past, Our Future” (OPOF) projects. There is still much partnership work to do. For example, on education and engagement, tackling the constant problem of encroachments onto the common land, creating sustainable recreational space around the New Forest, and making New Forest roads safe.

Tier three – land use change projects at landscape scale. This could be used to scale up the heathland and wetland restoration work, the water catchment partnership, and the Green Halo. Restoring habitats from the damage inflicted by past development and better protecting the New Forest landscape from modern day pressures; acquiring and restoring new land adjacent to the New Forest, as the National Trust have done at Foxbury and the RSPB at Franchises Lodge.

A steady start?

This is an exciting agenda, and the New Forest is well-placed to benefit from it. As ever, the details matter, and navigating the transition will be a considerable challenge, particularly for the CDA as a voluntary group reliant on individuals giving their time and attention to this important task. With the Verderers and National Trust HLS agreements now extended, and if we can obtain a declaration on the “Reference Period” for transition BPS payments, we will at least be off to a steady start.

The February 2020 DEFRA “Farming for the Future: Policy and Progress Update” is available here.

The February 2020 DEFRA “Environmental Land Management: Policy discussion document” is available here.

The DEFRA consultation on the Environmental Land Management policy discussion is open until 5th May, and can be accessed here.

The Agriculture Bill, and details of its progress through Parliament, can be found here.

by Tony Hockley, New Forest Commoners Defence Association

“You are amazing. We bow down to you. We are trying to emulate what you are doing!”

In his opening words to a Lyndhurst meeting organised by the Friends of the New Forest the leading light of the British rewilding movement, Charlie Burrell, paid homage to the New Forest as a unique survivor of Britain’s ancient wild landscape. The owner of the now famous Knepp Estate in West Sussex revealed a quite surprising lack of knowledge of the New Forest, given the proximity of Knepp. Indeed, he was surprised to discover how close the Forest was to Southampton. Perhaps this is part of the natural tendency in Britain to look abroad for inspiration, and ignore the everyday extraordinary landscapes on your doorstep. Perhaps this is part of the New Forest’s problems, that its special qualities are so easily overlooked. This was a point made later in the meeting by Diana Westerhoff, Natural England’s appointee to the New Forest Court of Verderers: Much of what is so special and so rare in the New Forest can be hard to spot for the untrained eye, citing the examples of the multiple lichens that need hard-grazed lawns to survive.

Rewilding at scale

To Charlie Burrell the scale of the New Forest free of fencing presents a vision of what could be achieved if experiments such as Knepp could be replicated on a larger scale, allowing the large herbivores to roam at will. Even the New Forest is a minnow in comparison to the truly wild landscapes of places like Yellowstone in the US. He explained the balance between scale and management intervention, so that the degree of active management required can decline as scale rises. Although 114km of internal fences have been removed at Knepp, so that the estate now has just three “blocks” of former agricultural land, each of the three is managed differently, with grazing by pigs, ponies, cattle, and deer. Rewilding he said is “process led”, with no defined end-game, but seeing where nature leads. The estate now has about 700 deer grazing, including red deer which found their way there rather be introduced with the smaller species, given the initial concern that an injury to someone using a footpath could threaten the project. The deer, he said, are essential “fight back” against the vegetation, “to ring bark trees” and help maintain the open landscape.

The desire to introduce wild boar to Knepp was prevented by legislation of dangerous wild animals, but this did not stop Charlie Burrell wondering aloud whether bison might help the New Forest educate the public on behaviour in an open access landscape. Perhaps, one day they could be introduced on rewilded land adjacent to the New Forest, and maybe one day the fences would come down, so that the bison could start to change attitudes to wild landscapes and “rewild us”.

© Sally Fear

Much of the questioning put Diana Westerhoff, in the hot seat, as a proxy representative for Natural England. She explained the current conflict between the Rural Payments Agency (RPA) which excludes gorse from the New Forest’s “eligible area” for support under the EU Basic Payments Scheme, and Natural England’s recognition of gorse as a vital habitat as part of the grazed New Forest. Additionally, poor funding for Natural England means that it can do much less monitoring than desired in this protected landscape. Charlie Burrell commented that, despite the appearance of an RPA takeover of Natural England the appointment of Tony Juniper as the chair of Natural England means “there is hope”.

Our moment in time

Much of the questioning related to claims of “overgrazing”, including a lack of tree regrowth in pasture woodland, and suggestions that nature was in decline in the New Forest (One questioner was also under the false impression that ivermectin wormers are used in Forest livestock). Diana Westerhoff directly addressed these beliefs emphasising the multiplicity of competing species, many only visible to the expert eye,whereas Charlie Burrell pressed the need to take a long view for wild landscapes, where grazing pressures rise and fall over time. This is, he argued, “Just a moment in time. It doesn’t matter”. Movement and change, he said, takes place over a very long time.

Rewilding People

Perhaps the topic of greatest consensus was education. Charlie Burrell told of young farmers visiting Knepp who were unable to identify common trees and Debbie Tann from the Hampshire and Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust pressed a case for “rewilding people”. This is, she said, made harder by plans for excessive housing development around a protected landscape and widespread misinterpretation of the word “park” in “National Park”. Charlie Burrell noted that the greatest problem from visitors stems from dog walking, particularly with regard to ground-nesting birds.

Inspiration for the Future New Forest

What messages did the discussion carry for commoning? It certainly emphasised the value of redoubling efforts started under the New Forest’s current “Our Past Our Future” (OPOF) landscape partnership, funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund. Not only is an Education Toolkit, bespoke for the New Forest, now being introduced to the curriculum in local schools, but the CDA’s Shared Forest project is finding new ways to engage with local people and businesses, and to share messages about valuing and protecting this very special landscape.

It also emphasised a need not only for enhanced monitoring of New Forest biodiversity, but also much better communication of what is already being achieved. Other OPOF partners are doing fabulous work on improving and monitoring biodiversity; not least the Freshwater Habitats Trust whose research is revealing not only the extraordinary cleanliness of ponds and streams in this traditionally grazed landscape but also the success of some of the little-known but exceptionally rare species that survive here but are all but wiped out elsewhere. There are also wonderful data coming from organisations such as Buglife and Plantlife, that need to be shared more widely. Monitoring of wetland restorations taking place under the Verderers’ Higher Level Stewardship (HLS) scheme are also now in the monitoring phase and evidence from these should be very useful as a guide to future management.

As these projects draw to a close the rewilding discussion has certainly hinted at some interesting initiatives that could be supported by a future Lottery bid and by whatever agri-environment scheme replaces the EU Basic Payments Scheme and HLS; better protecting some of the most tranquil and fragile habitats and species, experimenting with a variety of management regimes across the Forest’s amazing mosaic of habitats, and in the substantial enclosed lands of the New Forest (including commoners’ back-up grazing). The CDA has, of course, been working closely with its local and national partners to ensure that future support is best able to benefit the New Forest for future generations to appreciate and enjoy. This is certainly an exciting prospect in what Michael Gove described as an “unfrozen moment”.

This was all wonderful food for thought. Meanwhile we press on with “rewilding us”.

Members Login

Latest Tweets

Latest Tweets

Follow us

@realnewforest 4h

Icilibus sam quas aut eriatem nume corepta auta conet officaborem quodi corepta auta conet officaborem quodi apernat ectlpa dolorpiaecus.

@realnewforest 4h

Icilibus sam quas aut eriatem nume corepta auta conet officaborem quodi corepta auta conet officaborem quodi apernat ectlpa dolorpiaecus.

@realnewforest 4h

Icilibus sam quas aut eriatem nume corepta auta conet officaborem quodi corepta auta conet officaborem quodi apernat ectlpa dolorpiaecus.

With thanks for support from