Tony Hockley, CDA Chair

27th February 2020

The Government has now offered more clues regarding post-Brexit agricultural and environmental policies. These will be made possible by legislation now making  its way through parliament. The February 2020 farming policy update and a discussion paper on future environmental land management give some cause for hope in terms of continued investment in the New Forest; perhaps even a degree of quiet confidence that the local partnership work of recent years could continue to develop and grow under a new system. As ever in times of change,

its way through parliament. The February 2020 farming policy update and a discussion paper on future environmental land management give some cause for hope in terms of continued investment in the New Forest; perhaps even a degree of quiet confidence that the local partnership work of recent years could continue to develop and grow under a new system. As ever in times of change,  however, the transition from one system to another also brings very real risks. The biggest of these risks could be reduced quite easily, but it seems hard to get the New Forest voice heard in Whitehall. The dither and delay on the fate of the Verderers HLS does not inspire confidence in decision-making, and suggests we will need to shout more loudly, and much more early.

however, the transition from one system to another also brings very real risks. The biggest of these risks could be reduced quite easily, but it seems hard to get the New Forest voice heard in Whitehall. The dither and delay on the fate of the Verderers HLS does not inspire confidence in decision-making, and suggests we will need to shout more loudly, and much more early.

Dither & Delay: Decision on the Verderers HLS

Exactly one month before the expiry of the Verderers Higher Level Stewardship (HLS) scheme, the Rural Payments Agency finally agreed that this 10-year scheme would roll forward for a year from its February end date, as had happened in 2019 for the National Trust commons HLS. The roll-forward for the Crown lands of the New Forest could now last for up to four years, but decided annually. This may provide a bit of a cushion against the inevitable risks involved in the phase-out of the Basic Payments Scheme support from 2021, affecting many commoners. Nevertheless, several other landholdings in the open Forest have seen their HLS schemes come to an end, so that they are no longer within any form of “environmental stewardship”. The long delay to confirmation has had real impact; key staff from the incredible projects funded by the HLS have been lost due to the uncertainty over their roles, and the challenge of recruiting new expert staff with only short-term funding will be significant. The wetland and heathland restoration projects, and the New Forest Land Advice Service require real, local expertise if they are to continue at their previous pace.

The delay to confirmation of the HLS really was inexcusable given all that has been achieved by the Verderers HLS. This is the biggest agri-environment scheme in England, and one of the most innovative. Lowland heath is one of the rarest habitats in the world, more rare than rainforest, and still being lost. The New Forest is a prime, surviving example. The HLS has enabled parts of the open Forest that were lost to Forestry Commission conifer planting in the 20th Century, to be restored as fantastic grazed habitats, with incredible biodiversity and huge carbon storage capacity. If the Government is looking for an existing demonstration site for the Government’s ambition of using “public money for public goods”, then the Verderers HLS would be a leading candidate. That the HLS came within 30 days of ending with no viable alternative to replace it was simply ridiculous.

The Verderers HLS also supports a “Grazing Scheme”, offering practical support to New Forest commoning. Direct financial support is tailored to local priorities, with a fixed cap on the amount that can be received by any commoner, giving the greatest support where it is need to mitigate the additional costs of cattle-keeping, along with the provision of a few carefully-targeted cattle “feeding areas” to support cattle herds. It has also helped bring down the number of animals lost to traffic on the roads by providing thousands of reflective collars for ponies and cattle. That all of this can now continue whilst a new system of financial support is devised and introduced is a considerable relief.

Phasing out the Basic Payments Scheme

Anyone familiar with the governance of the New Forest will know that the CAP Basic Payment Scheme is something of a blunt instrument, ill-suited to the needs of this unique landscape. Nevertheless, it has played a vital role in sustaining cattle grazing in particular, following a period in which there was widespread concern that cattle commoning was dying out; threatening the many rare species that depend upon it. The BPS years have enabled commoners to invest in their back-up land and facilities, despite living in Britain’s least affordable national park, and despite the lure of profitable alternative uses of enclosed land within a very popular national park.

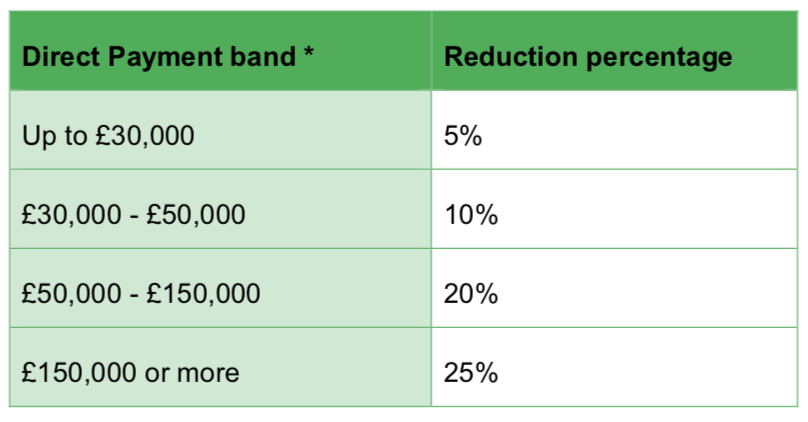

Proposed BPS reductions in 2021

Government policy is that BPS support will gradually be phased out from 2021 to 2027, to be replaced from 2024 by new Environmental Land Management Schemes (ELMS). In the interim new approaches will be tested, funded by the BPS reductions. The policy is that those who receive the most will be first in line for significant cuts to BPS. At present only the year one reductions have been announced. This process does mean that the financial impact on New Forest commoning may not be seen for several years, as the majority of commoners who do claim support under the BPS are at the bottom end of the scale, so will face small initial reductions in the amount they receive for their commoning commitments. Of course, most commoners already subsidise their communing from their day jobs, so that reliance upon the BPS within household income will often be lower than for farmers elsewhere: In this regard New Forest commoning is probably already one of the most diversified farming activities, supported (out of necessity) by multiple income sources and a large “leisure” time commitment.

The end of “mapping”

Some of the practical impact of change, however, will come very soon. From 2021 BPS payments will be “delinked” from the eligible land. This will finally end the nonsense of mapping the “eligible area”; a daft process which, for example, excludes areas of gorse from the grazing land. Gorse is an important habitat on lowland heath and valuable fodder for commoners’ animals. Following this “delinking” the hypothetical amount from which transition payments will be calculated will be based on a “reference period”. The sooner the reference year is set, the better. Knowing that there will be a “reference period” but not knowing what year or years it will be just creates a powerful perverse incentive to maximise the number of animals marked. For the New Forest this creates a huge workload for the agisters, marking animals that will never graze the New Forest. This undermines the credibility of the marking register as a record of grazing levels and the health of the commoning system. With a fixed pot of funding for the eligible New Forest area, this inflationary effect simply punishes responsible commoners: As the number of animals marked increases, the amount received per animal falls. This prospect is made even worse by the suggestion that the amount due for the entirety of the transition years could be taken as a single lump-sum. The perverse incentive in this situation is huge. In this time of uncertainty we will need to sustain the responsible, committed commoners who will stick with the practice whatever comes next, not those who will take the money and run. Even worse some current BPS claimants using New Forest entitlements may take the money pot and and also take the scarce back-up land that they use out of commoning, perhaps putting it to lucrative recreational use. The scarcity of back-up land has long been a practical threat to the continuation of commoning. Every animal turned out to graze must have someone to be kept if and when it is taken off the open Forest.

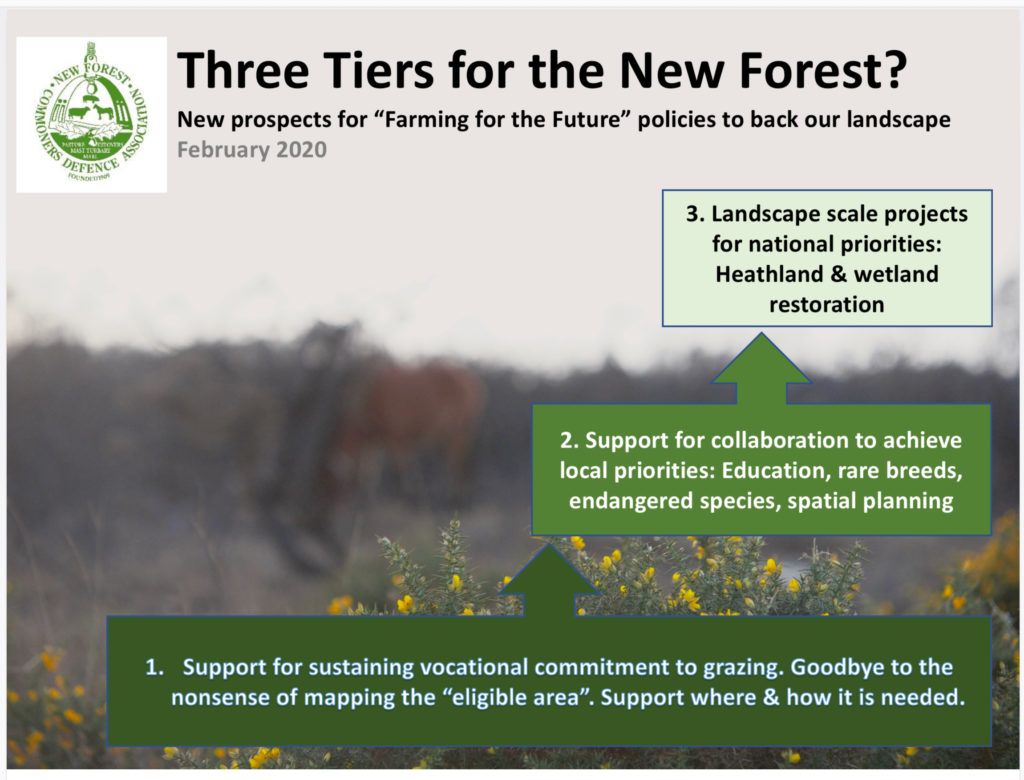

The Future: One scheme, three tiers?

Once the immediate risks of the transition are dealt with then our attention can turn to the new scheme. DEFRA are suggesting three tiers. The diversity of the New Forest, and the breadth of the public goods it offers, seems to suggest that all three tiers should apply.

Tier one- Encouraging environmentally sustainable farming. This seems the obvious basis for core but conditional support for good commoning practice, similar in some ways to the Verderers Grazing Scheme; backing high standards of animal and land management, delivering multiple public goods on the Forest and on commoners’ back-up land. As for upland commoners, it will be vital that individual commoners receive directly support for the valuable work they do, and the considerable pressures they must withstand.

Tier two – Delivering locally-targeted environmental outcomes. This could follow on from much of the species and habitat-specific collaborative project work that has taken place under the various HLS schemes and within the National Lottery Heritage Fund landscape partnership “Our Past, Our Future” (OPOF) projects. There is still much partnership work to do. For example, on education and engagement, tackling the constant problem of encroachments onto the common land, creating sustainable recreational space around the New Forest, and making New Forest roads safe.

Tier three – land use change projects at landscape scale. This could be used to scale up the heathland and wetland restoration work, the water catchment partnership, and the Green Halo. Restoring habitats from the damage inflicted by past development and better protecting the New Forest landscape from modern day pressures; acquiring and restoring new land adjacent to the New Forest, as the National Trust have done at Foxbury and the RSPB at Franchises Lodge.

A steady start?

This is an exciting agenda, and the New Forest is well-placed to benefit from it. As ever, the details matter, and navigating the transition will be a considerable challenge, particularly for the CDA as a voluntary group reliant on individuals giving their time and attention to this important task. With the Verderers and National Trust HLS agreements now extended, and if we can obtain a declaration on the “Reference Period” for transition BPS payments, we will at least be off to a steady start.

The February 2020 DEFRA “Farming for the Future: Policy and Progress Update” is available here.

The February 2020 DEFRA “Environmental Land Management: Policy discussion document” is available here.

The DEFRA consultation on the Environmental Land Management policy discussion is open until 5th May, and can be accessed here.

The Agriculture Bill, and details of its progress through Parliament, can be found here.

Forestry England “celebrates” its centenary this year. It will be much less of a celebration amongst those who care for the New Forest. Austerity has seen significant real cuts to Forestry England’s budget in recent years, although it still receives some £45 million of taxpayers’ money to carry out its core work. The New Forest is paying a heavy price as Forestry England seeks to maximise revenue and minimise its costs. Far from putting the Forest first it is turning back the clock to its original purpose of profit instead of protection.

The origins of Forestry England lie in the devastating exploitation of the New Forest. But around the start of the 21st century it came to appreciate the fragility of the landscape and the commoning system upon which it depends. Its own Land Agent produced the “Illingworth Report” for the government in 1991, seeking ways to sustain the grazing of the New Forest, and upon which everything else depends. But now it appears to be returning to its exploitative, uncaring roots. It is becoming a typical large-scale landlord: Distant, disinterested, and non-communicative. Anyone who has tried to contact Forestry England outside of office hours will know full well the low level of attention.

The origins of Forestry England lie in the devastating exploitation of the New Forest. But around the start of the 21st century it came to appreciate the fragility of the landscape and the commoning system upon which it depends. Its own Land Agent produced the “Illingworth Report” for the government in 1991, seeking ways to sustain the grazing of the New Forest, and upon which everything else depends. But now it appears to be returning to its exploitative, uncaring roots. It is becoming a typical large-scale landlord: Distant, disinterested, and non-communicative. Anyone who has tried to contact Forestry England outside of office hours will know full well the low level of attention.

Forestry England appears to have reversed the three objectives set out in the Minister’s Mandate for its management of the Crown lands. The primary objective of conservation is now subservient to the third objective of income generation and efficient management. In the Ministers Mandate it is made explicit that Forestry England’s commercial interest must only be pursued where it is consistent with conservation: “Forest First” is the official mantra. In truth, the book-keepers of Forestry England’s Bristol HQ are now the priority, not this precious landscape which they are paid by taxpayers to conserve.

The most blatant example of the new commercial agenda has been in the total disregard for government policy on the management of Crown properties within the Forest. For generations these have provided the bedrock of commoning: The Commission providing employment, and smallholdings for rent, for commoners. As commercial forestry declines the policy requires that these are prioritised to continue to support commoning, made available to commoners (whether Commission employees or not) at affordable rents. In October 2017 ministers reminded Forestry England that policies can only change if ministers decide to do this. This has been ignored completely. Instead it has continued to move all properties to unaffordable market rents, approaching £2000 a month, and prioritising their use as a perk for its own employees. It is setting rents that are at least 70% of average local household incomes, and more than 100% of most young commoners’ incomes. This is no different to a local authority deciding to hand social housing to its managers. In just three months at the end of 2018 the keys for three commoners’ holding were handed to Commission staff, none of whom were commoners. Others are standing empty, but the desire to maximise revenues gives little hope of any being used to support the continuation of commoning.

In 2006 DEFRA ministers stated that the proportion of cottages rented to commoners would increase. It is now in rapid decline. In the past three months alone three excellent commoners’ holdings have been handed to Forestry England employees, who have been told that they will go on the open market if not taken up at rents of £18-24,000 a year. It is now advertising a cottage for £1450 a month for commoners with a minimum of 10 ponies, yet providing little more than one acre of back-up. The criteria are as arbitrary as the rent. It is designed to fail so they can take it onto the holiday homes market. The CDA have been discussing these concerns with Forestry England for three years, but they have ploughed on with the new strategy regardless. It is hard to overstate the damage being done to the sustainability of the New Forest landscape by the loss of these prime commoning holdings. The cottages were retained in these locations for a purpose, but one by one commoners are being forced out of the Forest and the direct contribution of these properties to the local Forest is being lost. Forestry England argues that extreme property values in the New Forest mean that affordable rents are nothing more than an intolerable “opportunity cost” for its Bristol book-keepers, that anything below open market rents is an unaffordable subsidy. For commoners who subsidise their livestock through their own time and income, and whose taxes fund Forestry England, these claims add insult to injury.

The unilateral abandonment of a “Forest First” strategy is also visible in the increasingly aggressive management of its campsites in the New Forest. According to recent Annual Reports for Camping in the Forest LLP, the “key strategic focus” for this new joint venture for the campsites on the Open Forest SSSI is to “grow pitch nights”, against which the protected status of this land is described as the “principle risk” facing the business.

In 2019 Forestry England celebrates its centenary, with its latest rebranding from Forestry Commission. It seems that it is also reverting to its original 1919 mission, to simply maximise its exploitation of the landscape. The New Forest seems to be little more than a local irritation, that requires financial support, diverting the agency from its relentless pursuit of revenues. In 2011 the country thought it had fought off forest privatisation. It now seems that the same outcome is being achieved under the radar. No-one within the Forestry Commission seems able to act as a voice for the New Forest, and the Minister’s Mandate is simply withering on the vine.

Commoners have fought off similar threats over centuries. We have no intention of standing by and letting them happen today.

10 FACTS ABOUT THE CROWN HOLDINGS IN THE NEW FOREST

- There are around 65 Crown properties in the New Forest, originally built for forestry, and now managed by Forestry England on behalf of the Department of the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs

- In the late 1980s a thorough New Forest review for Government concluded that the best way to maintain the New Forest landscape was to support the vocational system of small-scale commoning. The Illingworth Report set a policy, endorsed by ministers, that forestry properties in the New Forest would be retained to provide bases for commoning and rented to them at 15% of income given the local disparity between incomes and rents.

- This policy was repeated in 2006, when DEFRA minister, Ben Bradshaw, said that the cottages had been retained for commoning, and that an increasing proportion would be allocated to commoners as Forestry operational needs decline

- In 2016 Forestry England unilaterally declared a policy to move land and holdings towards market rents for all tenants

- In October 2017 DEFRA minister Dr Therese Coffey responded to a question from Desmond Swayne MP (New Forest West) confirming that any change from the Illingworth policy would require full consultation and a proposal put to ministers for approval

- In July 2018 the Assistant Land Agent emailed all local Forestry England staff offering currently vacant cottages at rents between £18000 and £24,000 per annum, regardless of local operational need, and with no preference for staff who would graze livestock from the holdings. The email stated that any holdings left would then be let on the “open market”, with no mention of commoning. This email was leaked to us.

- In May 2019, under pressure from the CDA, Forestry England decided to offer one smallholding to commoners, by a tender process with an advertised price of £18,000 a year. They imposed a requirement to graze 10 ponies, despite the holding having just 1 acre of back-up land and three pony stables, grossly insufficient for the care of 10 animals. They also chose to separate the barn from the property in order seek a commercial tenant, leaving the holding with no facility for the storage of hay or equipment.

- For three years the CDA has sought to discuss this matter with Forestry England and been willing to update the Illingworth policies to reflect changes in the housing market. Forestry England have simply continued to implement its open market and market rent policies

- The average local property value in the New Forest has now reached a multiple of 15.9 times average local income. The national park premium for a property within the New Forest is now £300,000. It is Britain’s least affordable national park

- In May 2019 the New Forest Trust charity obtained planning permission for one small rental holding, which will be built after a local fundraising campaign, and which is already heavily oversubscribed by young commoners in need of an affordable base within the New Forest.

Members Login

Latest Tweets

Latest Tweets

Follow us

@realnewforest 4h

Icilibus sam quas aut eriatem nume corepta auta conet officaborem quodi corepta auta conet officaborem quodi apernat ectlpa dolorpiaecus.

@realnewforest 4h

Icilibus sam quas aut eriatem nume corepta auta conet officaborem quodi corepta auta conet officaborem quodi apernat ectlpa dolorpiaecus.

@realnewforest 4h

Icilibus sam quas aut eriatem nume corepta auta conet officaborem quodi corepta auta conet officaborem quodi apernat ectlpa dolorpiaecus.

With thanks for support from